Citizenship and the 2020 Census

On January 15, 2019, Judge Jesse Furman, a federal district court judge in New York, issued a 277-page opinion overruling the decision of the Secretary of Commerce, Wilbur Ross, to add a citizenship question to the 2020 census. The decision followed a five-month discovery process, an eight-day trial, extensive post-trial briefing, and closing arguments. Based upon the evidence before him, Judge Furman concluded that Secretary Ross violated both the law and the public trust.

Unfortunately given today’s constantly cascading news cycles, the decision itself and the story of how Secretary Ross’ decision came to be made and its implications for the 2020 census were largely lost on the public. However, as told by Judge Furman’s own extensive findings of fact and law, the story deserves much greater attention as it demonstrates how the public interest can be potentially subverted by efforts founded on political goals rather than good government.

~~~ ~~~ ~~~ ~~~ ~~~ ~~~ ~~~

The Constitution mandates that an “actual Enumeration” be conducted “every . . . ten Years, in such Manner as [Congress] shall by Law direct,” an effort now commonly known as the census, or, more precisely, the decennial census. (Art. I, § 2, cl. 3.) By its terms, every ten years the federal government must endeavor to count every single person residing in the United States, whether citizen or non-citizen, whether living here with legal status or without.

The original purpose of this “Enumeration” was to apportion congressional representatives among the states “according to their respective Numbers.” Today, however, its impact is far greater. Among other things, the census count affects the allocation of electors to the Electoral College, the division of congressional electoral districts within each State, and the apportionment of state and local legislative seats. The census results also directly control the distribution of hundreds of billions of dollars of federal funding each year to both States and localities. It is for all of these reasons that the census has been described by Congress itself as “one of the most critical constitutional functions our Federal Government performs.”

Congress has assigned its constitutional duty to conduct the census to the Secretary of Commerce and the Census Bureau, today a part of the Commerce Department. The Secretary’s fundamental obligation is to obtain a total-population count that is as accurate as possible, consistent with the Constitution and the law. The Bureau conducts the required enumeration principally by sending a short form questionnaire to every household.

The questions posed on the short form census have ebbed and flowed since the first census in 1790 asked each household about “the sexes and colours of free persons,” as well the age of each resident. Most relevant here, a question regarding citizenship appeared for the first time on the fourth census in 1820, when Congress directed enumerators to tally the number of “Foreigners not naturalized.” With one unexplained exception (the 1840 census), a question about citizenship status or birthplace appeared on every census thereafter through 1950.

That changed in the 1960 census. That year, only five questions were posed to all respondents, concerning the respondent’s relationship to the head of household, sex, color or race, marital status, and month and year of birth. In a review of that census several years later, the Census Bureau explained the decision not to ask all respondents about citizenship as follows: “It was felt that general census information on citizenship had become of less importance compared with other possible questions to be included in the census.”

Beginning in 1960, the decennial census questionnaire sent to every household has not included any question related to citizenship status. In both Republican and Democratic administrations, the Census Bureau has vigorously opposed adding any such question because of its concern that doing so would depress response rates, including those of non-citizens and immigrants, thereby undermining the accuracy of the headcount. The Bureau concluded that questions designed “to ascertain citizenship will inevitably jeopardize the overall accuracy of the population count” because such questions “are particularly sensitive in minority communities and would inevitably trigger hostility, resentment and refusal to cooperate.” Census Bureau directors appointed by presidents of both political parties have agreed. (See Endnote 1.)

~~~ ~~~ ~~~ ~~~ ~~~ ~~~ ~~~

In March 2018, Secretary Ross announced that he had decided to add a citizenship question to the 2020 census short questionnaire. In a memorandum announcing this decision, Secretary Ross stated that he only “began” considering adding a citizenship question after receiving a letter from the Department of Justice, dated December 12, 2017, requesting citizenship data from the census in order to enforce the Voting Rights Act (VRA). The Secretary reiterated in subsequent congressional testimony that the citizenship question on the 2020 short form census “is necessary to provide complete and accurate data in response to the DOJ request.” And the Secretary also stated that he was “not aware” of any discussions between himself and any White House officials about the citizenship question.

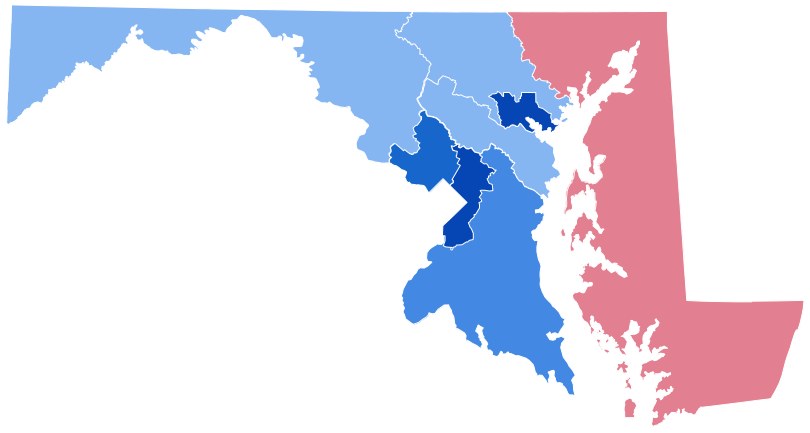

Eight days after Secretary Ross’s March 26, 2018 memorandum announcing his decision, a case challenging the decision was filed by a coalition of governmental entities, including 18 states (Maryland being one of them), the District of Columbia, and 15 cities and counties. These governmental entities all alleged that Secretary Ross’s decision to include a citizenship question violated the Administrative Procedure Act (APA). The APA “sets forth the procedures by which federal agencies are accountable to the public and their actions subject to review by the courts.” (See Endnote 2.)

~~~ ~~~ ~~~ ~~~ ~~~ ~~~ ~~~

According to Judge Furman, the evidence disclosed at trial revealed that Secretary Ross’s description of the citizenship decision was “materially inaccurate.” In fact, “a very different set of events” had occurred as described in painstaking detail in his opinion.

In particular, the evidence showed that shortly after his confirmation as Secretary of Commerce, Secretary Ross discussed the addition of the citizenship question with then-White House advisor Steve Bannon, among others; that Secretary Ross wanted to add the question to the 2020 census prior to, and independent of, the DOJ’s December 12, 2017 request; that the Secretary and his political aides pursued that goal vigorously for almost a year, with no apparent interest in promoting more robust enforcement of the VRA. Then, after becoming convinced that they needed another agency to request and justify a need for the question, Secretary Ross and his political aides worked hard to generate such a request for the citizenship question from both the Department of Homeland Security and the DOJ. Frustrated at the delay in the receipt of an affirmative response from DOJ, Secretary Ross directly intervened by a phone conversation with Attorney General Sessions which resulted in the DOJ’s request for a citizenship question. In setting up the phone call, an aide to Sessions emailed Ross’ chief of staff saying that “it sounds as if we can do whatever you need us to do. The AG is eager to assist.”

Based upon trial testimony and documentary evidence, Judge Furman held “while the Court is unable to determine—based on the existing record, at least—what Secretary Ross’s real reasons for adding the citizenship question were, it does find, by a preponderance of the evidence, that promoting enforcement of the VRA was not his real reason for the decision.” (See Endnote 3.) Secretary Ross and his political aides aimed to “launder” their request through another agency—that is, to obtain cover for a decision that they had already made—and the reasons underlying any request from another agency were “secondary, if not irrelevant.”

The trial record also revealed that Secretary Ross’s decision had been made in contravention of the Census Bureau’s long-held opposition to such a question, which continued. Following the receipt of the DOJ letter, the Census Bureau, including the Bureau’s Chief Scientist, concluded that adding the question would “harm the quality of the census count” by “reducing the self-response rate,” thereby increasing the Bureau’s costs and harming the overall data and integrity of the census.

Judge Furman concluded that the evidence in the trial record “overwhelmingly” supported the conclusion that the addition of a citizenship question to the 2020 census would cause a significant net differential decline in self-response rates among households with at least one non-citizen and that the Bureau’s follow-up procedures aimed at non-responding households would fail to cure that decline. More specifically, he found that the addition of a citizenship question to the 2020 census would cause an incremental net differential decline in self-responses among non-citizen households of at least 5.8%. He further opined that that estimate is “conservative and that the net differential decline could be much higher.” The implementation of the Bureau’s follow-up procedures for non-responding households would simply replicate all of the same effects on non-citizen response that will cause the decline in self-response in the first place.

On the merits, Judge Furman determined that Secretary Ross had violated the APA in multiple independent ways—“a veritable smorgasbord of classic, clear-cut APA violations.” Secretary Ross’s decision to add a citizenship question was “arbitrary and capricious” on its own terms. He failed to consider several important aspects of the problem; alternately ignored, cherry-picked, or badly misconstrued the evidence in the record before him; acted irrationally both in light of that evidence and his own stated decisional criteria; and failed to justify significant departures from past policies and practices. Finally, the evidence establishes that Secretary Ross’s stated rationale—to promote VRA enforcement—was just a pretext. In other words, that he announced his decision in a manner that concealed its true basis rather than explaining it, as the APA required him to do.

As further described by Judge Furman, “these violations are no mere trifles.” The fair and orderly administration of the census is one of the Secretary of Commerce’s most important duties, and it is critical that the public have “confidence in the integrity of the process.” (See Endnote 4.)

It should also be noted that four former Census Bureau Directors opposed the addition of a citizenship question. They and two other former Directors wrote to Secretary Ross to express “deep concern” about the addition of such a question. In addition, five of the six former Directors filed an amicus brief in support of Plaintiffs in these cases and the sixth, John Thompson, testified as an expert witness on Plaintiffs’ behalf.

The current professionals in the Census Bureau also concluded that the DOJ’s stated interest in having more granular citizenship data could be satisfied in a less costly, more effective and less harmful manner. The evidence reveals that at the express direction of Attorney General Sessions, DOJ deliberately (and unusually) refused to meet with representatives of the Census Bureau to discuss the Census Bureau’s conclusion.

Appeals from Judge Furman’s decision by the Department of Justice have already been made to both the Second Circuit Court of Appeals and to the Supreme Court. In fact, the Solicitor General has urged the Supreme Court to resolve the appeal prior to any judgment of the Second Circuit, which would ordinarily rule before the Supreme Court. As a result, although the opinion of Judge Furman is an important chapter in this significant dispute, it is obviously not yet likely the last chapter. These appeals to Judge Furman’s decision against including a citizenship question will need to be resolved soon as the 2020 census is now less than a year away.

Endnotes:

- The Bureau has recently requested citizenship information through other means besides the decennial census questionnaire. However, such requests have gone to a limited number of individuals and thus have not raised the same concerns as does adding a citizenship question to the decennial census. Until 2000, the Bureau requested such information through a “long-form” census questionnaire—a list of questions sent each decade to just one of every six households. In 2005, the Bureau replaced the long-form questionnaire with the American Community Survey (ACS), which contains more than forty-five questions and is sent annually to only one of every thirty-six households.

- Challenges to Secretary Ross’ decision also have been brought in four other cases in federal district courts in California and Maryland. Bench trials are ongoing in all four cases as this is being written.

- The DOJ vigorously opposed Judge’s Furman’s order allowing a deposition of Secretary Ross up to the Supreme Court which suspended the deposition until after briefs and oral argument on the issue. In light of the opinion of Judge Furman on the merits, the issue involving the deposition became moot.

- Although not directly relevant to Judge Furman’s ultimate opinion, it is worthy to note the unusual extent to which the Department of Justice endeavored to prevent or delay a decision on the merits of this issue. As Judge Furman noted, the defendants “tried mightily” to avoid a ruling. They asserted a slew of unsuccessful jurisdictional arguments, raised multiple challenges to this Court’s decisions authorizing discovery beyond the administrative record and tried no fewer than fourteen times to halt the proceedings altogether. Fortunately for the rule of law, these tactics failed to prevent the court from reaching the result described herein.

Common Sense for the Eastern Shore