Digital Inclusion on the Eastern Shore

At a time when schools are partially or totally online, medical appointments take place over Zoom, court proceedings happen virtually, and coronavirus vaccination appointments are scheduled via the internet, to be without these tools is more serious than just an inconvenience. Computers and internet access are essential, and people who lack these assets are at a great disadvantage.

The Abell Foundation released a report recently — Disconnected in Maryland — that analyzes the scope of this problem in the state and region. The report divides the Eastern Shore into the Upper and Mid-Shore (Caroline, Dorchester, Kent, Queen Anne's, and Talbot Counties), Lower Shore (Somerset, Wicomico, and Worcester Counties), and Cecil County.

The report looks at two measures of digital inclusion: access to wireline broadband internet service at home and possession of a computer at home with which to connect to the internet.

Broadband service refers to high-speed internet access. Wireline broadband is a subset, and includes DSL, cable, and fiber.

- Digital subscriber line (DSL) services transmit data to the home using traditional copper telephone wires; data transmission speeds are faster than dial-up but typically pretty slow for residential customers, averaging from 0.5 to 8 Mbps (megabits per second).

- Cable modem services provide internet access using the same coaxial cables that deliver picture and sound to your TV; faster than DSL, cable can have speeds of from 0.5 to up to 52 Mbps.

- Fiber optic technology converts data to light and sends that light through transparent glass fiber about the diameter of a human hair; speeds far exceed current DSL or cable modem speeds, up to a gigabite per second (10,000 Mbps).

According to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), to qualify as broadband, an internet service must deliver at least 25 Mbps download speed and at least 3 Mbps upload speed. This requirement disqualifies much DSL coverage from the broadband category, even though DSL is technically a wireline service. Importantly, the FCC figure is also the data speed requirement for much online school software. The report does not make the speed distinction, and so its estimates of broadband access are probably overstated.

The Eastern Shore has fewer connected households than Maryland as a whole. In the Upper and Mid-Shore counties, 36 percent of households do not have broadband subscriptions at home. On the Lower Shore, the figure is similar, at 35 percent of households. Twenty-seven percent of Cecil County households are without that access. In Maryland that figure is 23 percent.

The second measure of digital inclusion used by the report is possession of a computer (desktop or laptop) at home with which to connect to the internet. In the Upper and Mid-Shore counties and the Lower Shore counties, 23 percent of households do not have a computer at home. In Cecil County that figure is 20 percent. In Maryland it is 18 percent. Again, Eastern Shore households are worse off than Maryland as a whole. (Note: an additional 4 to 5 percent of households have access to a tablet at home.)

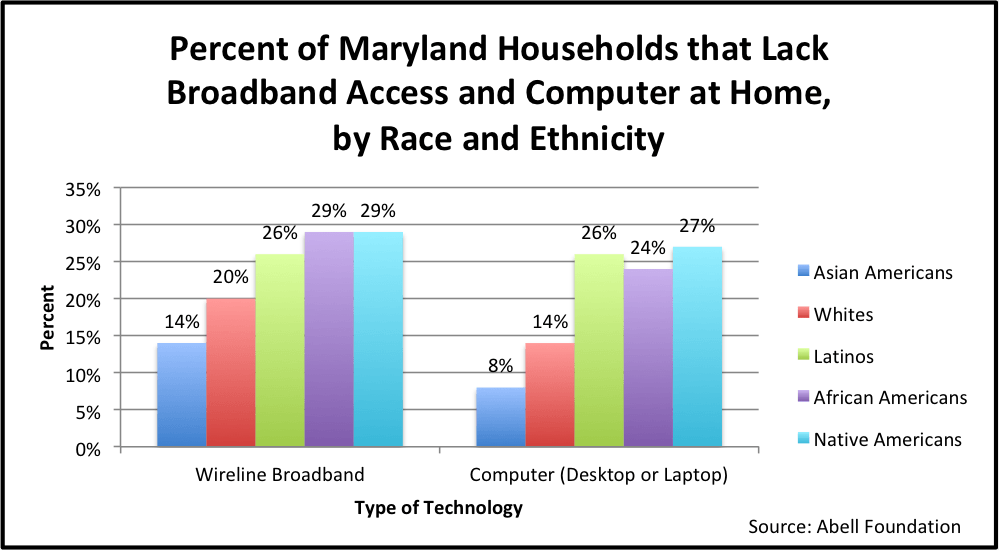

The Abell report also looks at statewide adoption of these technologies by income, race and ethnicity, age, and households with children under 18.

As expected, income is the greatest factor for whether a household has access to broadband and computers. Over half of households with incomes under $25,000 per year do not have broadband access at home, and nearly half do not have a computer at home. For households with incomes between $25,000 and $50,000 per year, over a third do not have broadband access at home, and 29 percent do not have a computer at home.

Broadband access and ownership of computing devices by African Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans are below state averages overall. A quarter or more of those households do not have broadband access or a computer at home.

Younger adults are more likely to have broadband access and computers. The gap in technology adoption is very large for people 75 and older. For all Marylanders 65 or older, over a third do not have broadband subscriptions at home and over a quarter do not have a computer. Seniors are disproportionally affected by the resulting inability to conduct medical appointments remotely and schedule covid-19 vaccinations.

In households with children under 18, a lack of technology has potential for widespread and long-lasting consequences when school is held virtually. Missing school and falling behind can result in dropping out of high school, and have long-term negative consequences for future employment and income potential.

In low-income households (income less than $50,000) with children under 18, nearly a third of households lack broadband access at home, and over a quarter do not have a computer at home. In Hispanic households with children under 18, almost a quarter do not have broadband access or computers at home. Nineteen percent of African American households with children under 18 do not have broadband access, and 15 percent do not have computers at home.

A recent McKinsey report on Covid-19 and Learning Loss states: “The pandemic has both illuminated and magnified the persistent disparities between different races and income groups in the United States. In education, the pandemic has forced the most vulnerable students into the least desirable learning situations with inadequate tools and support systems to navigate them.”

How can we address these problems? There are no short-term fixes for pervasive problems like these, but establishing a statewide Office of Digital Inclusion would be a step in the right direction.

Sen. Sarah Elfreth (D-Anne Arundel) and Del. Carol Krimm (D-Frederick) have introduced the Digital Connectivity Act of 2021 (SB66 and HB97), which would establish an Office of Digital Inclusion to ensure that every resident of Maryland has the ability to connect to reliable, affordable broadband internet by 2030, and has the tools necessary to use and take advantage of the internet.

This legislation could start to make a difference for many families on the Eastern Shore.

Jan Plotczyk spent 25 years as a survey and education statistician with the federal government, at the Census Bureau and the National Center for Education Statistics. She retired to Rock Hall.

Common Sense for the Eastern Shore