Is a Maryland Congressional District Unconstitutional? Maybe

Elections, the Census and the Constitution:

In 2020, there will be a presidential election about which many people on the Eastern Shore have an opinion. But next year another very important Federal action will take place: the US Government will carry out a national census as required by the US Constitution. Art. I, Sec. 2 states: “The actual Enumeration shall be made within three Years after the first Meeting of the Congress of the United States, and within every subsequent Term of ten Years, in such Manner as they shall by Law direct.”

There are fundamental reasons all levels of American government need to know the size of each state’s population. The one most relevant to this discussion is that the number of Congressional Representatives from each state is determined by population. In other words, each congressional representative should have approximately the same number of residents in her/his district. In 1788, just after the constitution was signed, that population per member of congress was 30,000. Now in 2019, the US population has grown so that each member of congress should represent about 700,000 people, if all districts are drawn equally.

However, the Constitution leaves the details of the elections and the exact shape of the Congressional districts, each containing some 700,000 people, up to the state legislatures.

Maryland, Gerrymandering and the US Supreme Court:

Not long after the US Constitution was ratified in 1788, state politicians realized that if a district was drawn to contain more people who supported them than those who did not, they could win more elections. However, it wasn’t until 1812 that a Massachusetts governor named Elbridge Gerry succeeded in pushing through a law creating a contorted Congressional district around Boston that contemporaries described as “a mythological salamander.” Gerry’s achievement has been memorialized down to the present day. All distorted, oddly-shaped districts designed for political advantage are described as “gerrymandered,” and the process of creating them is known as “gerrymandering.”

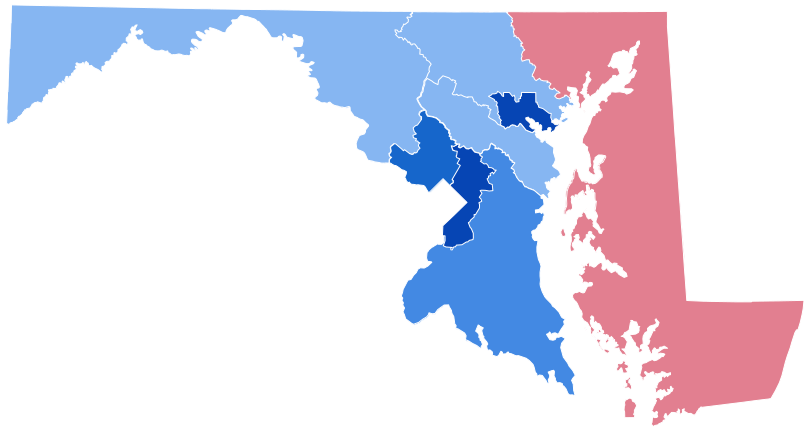

This brings us to accusations by Maryland Republicans that Democratic Governor Martin O’Malley in 2011 gerrymandered Maryland’s Sixth Congressional District to ensure that Congressman Roscoe Bartlett, a Republican in office for 20 years, would lose in 2012 to a Democrat. Bartlett had been re-elected in 2010 by a 28% margin. No question, the shuffling around of geography and population was quite successful.

A lawsuit brought by Republican voters challenging the redrawing of District 6 reached the US Supreme Court for review in its 2019 session. To be fair and balanced, the Supreme Court selected a companion case to hear during the same term, brought by North Carolina Democrats against a Republican Governor and Legislature who are accused of similar gerrymandering efforts.

Plaintiffs in both cases want the high court to order the maps to be redrawn before the 2020 election.

Does the Supreme Court’s Past Attitude toward Gerrymandering hint Decisions?

Gerrymandering is such a purely political act, and is so fraught with major social issues of discrimination, the Court has generally avoided defining “bad” gerrymandering because it would set a future precedent.

What the Court must consider this term, is whether the redistricting in either case violated the First Amendment by damaging the plaintiffs’ representational rights and other rights based on their party affiliation and voting history. It is a fairly high bar to overcome, but if the Court does so, the decisions could change how Congressional districts across America are drawn and thus could change who controls the US House of Representatives.

Common Sense for the Eastern Shore