Let My People Go: A Prophet’s Letter from Prison

“Let justice roll down like waters and

righteousness like an ever-flowing stream.”

Amos 5:24

Adversity can produce a powerful outcome. Such were the results of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s 13 days in the Birmingham, Ala., jail in April 1963.

There he wrote “Letter from Birmingham Jail” under difficult circumstances. Limited in writing supplies (he used newspaper margins and toilet paper), King produced a document that ranks with Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence, Washington’s Farewell, and Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address.

Civil rights activists had decided to move into Birmingham because of its violent segregation. Those planning to demonstrate were trained in nonviolent civil disobedience.

On April 12, eight Alabama clergymen published a “Public Statement” urging Birmingham’s “Negro community to withdraw support from these demonstrations.” On April 16, King and others were jailed because they defied a court injunction not to conduct a march.

Responding to criticism from the clergymen and with many religious references, King reminds us of Moses in Exodus 5, telling Pharoah to “let my people go.” The parallels between the Israelites enslaved in Egypt and 20th century Black Americans are obvious. (On the other hand, the “Slave Bible” first published in 1807, not surprisingly, removed nearly the whole Book of Exodus, thus making it an un-biblical Bible.)

One might argue that a secondary purpose of King’s “Letter” was to remind the clergymen and the public of vital parts of scripture. King quotes the prophet Amos in answering charges that he was an extremist: “Let justice roll down like waters and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream.”

Speaking of the prophetic tradition, Jeremy Taylor, Bible professor at Abilene Christian University, writes:

“King’s deep immersion in the Old Testament prophetic tradition keenly trained his eye to see the masses of poor African Americans who were being allowed to drown in the ocean of White wealth. Instead of his middle-class education in White institutions anesthetizing him to the plight of those trapped in the misery of poverty, King used his education to unleash the power of his mind and the spirit of the prophets to unleash his tongue in defense of the exploited.”

Taylor’s view persuades us that King was not like a prophet. He was one.

King makes much of the teachings in the New Testament. In his introduction to the “Letter,” he tells us that he follows the example of St. Paul in preaching the gospel beyond his hometown. And while Paul was imprisoned, he wrote letters. In 1956, King preached a sermon in Pittsburgh in which he took on the persona of Paul. King said, “you stand in the most segregated hour of Christian America,” chastising both Blacks and Whites for their segregation.

To explain the harm from racism King draws on the ideas of the Jewish theologian Martin Buber. “Segregation … substitutes an ‘I-it’ relationship for an ‘I-thou’ relationship and ends up relegating persons to the status of things.” King reminds us that, according to theologian Paul Tillich, sin is separation, separation between persons, and between God and persons.

One of the most important points comes from St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas: the distinction between just and unjust laws. An unjust law is one not based on eternal and natural law; it degrades people. King wrote, “Any law that uplifts human personality is just. Any law that degrades human personality is unjust. All segregation statutes are unjust because segregation distorts the soul and damages the personality. It gives the segregator a false sense of superiority and the segregated a false sense of inferiority.” An unjust law not only does harm, but it obligates us to disobey it: “One has not only a legal but a moral responsibility to obey just laws. Conversely, one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws.”

King’s conclusion to his “Letter” is uplifting: “Let us all hope that the dark clouds of racial prejudice will soon pass away and the deep fog of misunderstanding will be lifted from our fear drenched communities, and in some not too distant tomorrow, the radiant stars of love and brotherhood will shine over our great nation with all their scintillating beauty.”

Amen.

Further reading:

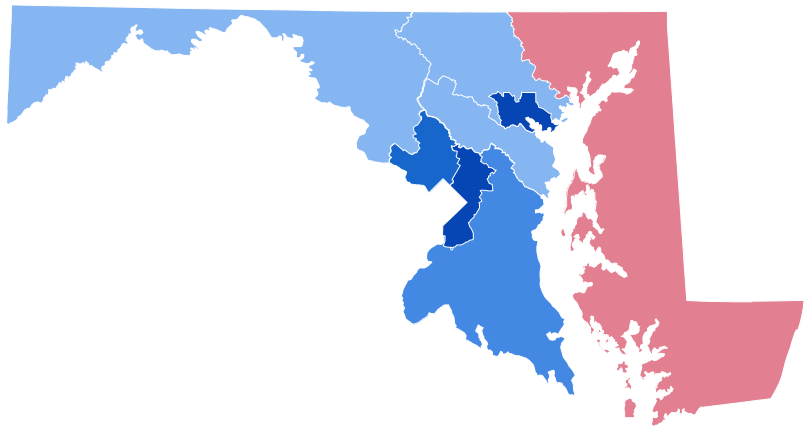

Jim Block taught English at Northfield Mount Hermon, a boarding school in Western Mass. He coached cross-country and advised the newspaper and the debate society there. He taught at Marlborough College in England and Robert College in Istanbul. He and his wife retired to Chestertown, Md., in 2014.

Common Sense for the Eastern Shore