Owners of Enslaved Persons on the Eastern Shore Who Served in the Maryland Legislature and in the U.S. Congress, Part 2

Excerpt from list of birthdates and deathdates of enslaved people. Image: Maryland State Archives

Part 1 of this series focused on owners of enslaved people in the lower Eastern Shore counties, Wicomico, Somerset, and Worcester, and who served in the state or federal legislatures. Part 2 considers five of the 12 enslavers who were also legislators and who resided in the Mid-Shore counties of Dorchester and Talbot:

1. Charles Goldsborough (1765-1834), Dorchester

2. Robert Henry Goldsborough (1779-1836), Talbot

3. William Hayward, Jr. (1787-1836), Talbot

4. Daniel Maynadier Henry (1823-1899), Dorchester

5. Thomas Holiday Hicks (1798-1865), Dorchester

6. William Hindman (1743-1822), Talbot

7. John Leeds Kerr (1780-1844), Talbot

8. Edward Lloyd (1779-1834), Talbot

9. Robert Nichols Martin (1798-1870), Dorchester

10. William Vans Murray (1760-1803), Dorchester

11. Richard Spencer (1796-1868), Talbot

12. Philip Francis Thomas (181-1890), Talbot

The names of these politicians are taken from a Washington Post project to identify enslavers.

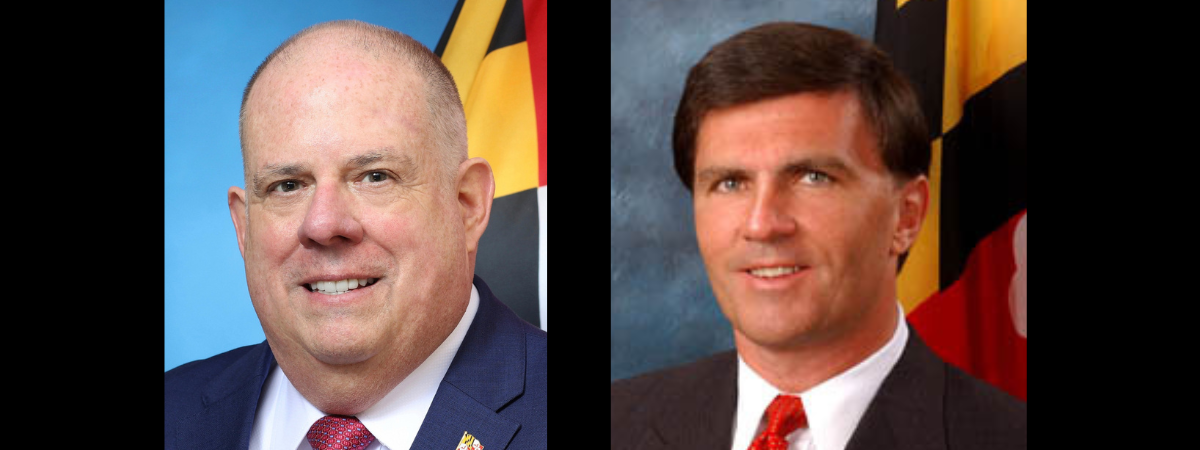

Charles Goldsborough. Image: Wikimedia Commons

Charles Goldsborough

Charles Goldsborough was born at “Hunting Creek” near Cambridge in Dorchester County. He graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 1784 was admitted to the Maryland bar in 1790. After holding several local offices, he served as a member of the state senate from 1791 to 1795 and 1799 to 1801.

He was elected as a Federalist to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1805 and served five consecutive terms until 1817. Goldsborough was also governor of Maryland in 1818-19. He retired from public life in 1820 to “Shoal Creek,” his country estate near Cambridge, and died there in 1834. He was interred in Christ Episcopal Church Cemetery in Cambridge.

Goldsborough was a major owner of enslaved men, women, and children. According to the federal census of 1830, Goldsborough held 116 people in bondage on his estate: 33 boys and young men; 16 men; 2 older men; 34 girls and young women; 16 women; 5 older women; and 10 of unknown ages.

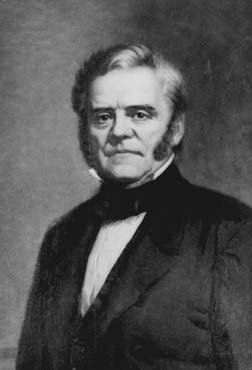

Thomas Holliday Hicks. Image: Maryland State Archives

Thomas Holliday Hicks

Born in East New Market, Dorchester County, Hicks began his political career as a constable in his hometown. A Democrat, he was then elected as the county sheriff. He then joined the Whig party and was elected to the Maryland House of Delegates in 1830 and re-elected in 1836.

In 1838, he was appointed register of wills for Dorchester County, the position he held until he was elected as governor in 1858. By then, the Whigs had disintegrated and he joined the Native American Party, more commonly known as the “Know-Nothings.” That election was notably corrupt, including open intimidation of voters and major violence.

In his inaugural address as governor, Hicks criticized the number of immigrants entering the country, claiming they would change the national character. He opposed the abolitionists, denouncing “the attacks of fanatical and misguided persons against property in slaves” and insisting that owners of enslaved people had a right under the constitution to recover their property.

In December 1862, his successor as governor appointed him to the U.S. Senate to complete the term of James A. Pearce, who had died. Hicks died in Washington D.C. in 1865 and was buried on the family farm in Dorchester County. His remains were later disinterred and moved to Cambridge Cemetery. The state placed a monument on his grave in 1868.

Hicks owned fewer enslaved persons than Goldsborough, a total of eight according to the 1840 federal census, including one boy, one man, two women, and four of unknown ages.

William Hindman. Image: Wikipedia

William Hindman

William Hindman was born in Dorchester County, but later lived in Talbot, where his father owned a plantation. He studied law at the Inns of Court in London, England, returning home in 1765. He was admitted to the Maryland bar and practiced in Talbot County.

He served in Maryland’s revolutionary government from 1775 to 1777 and as state treasurer for the Eastern Shore. He resigned that post when he was elected to the state senate in 1777, where he served until 1784. Maryland sent him as a delegate to the Continental Congress in 1785 and 1786.

From 1789 to 1792, Hindman served on the governor’s executive council. In the latter year, voters returned him to the state senate, from which he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives that same year after the resignation of Joshua Seney (another Eastern Shore enslaver from Queen Anne’s County). He served in the House until 1799. When Maryland’s U.S. Senator James Lloyd resigned in 1800, Hindman was named to finish his term, which ran until 1801. In the Senate, he was aligned with the Whigs. He died in Baltimore in 1822, and is buried in St. Paul’s Burial Ground.

The number of enslaved persons that Hindman held increased over the years. In 1790, he owned six, but by 1820, the total was 86, broken down as follows: 23 boys and young men; 23 men; 16 girls and young women; and 24 women.

John Leeds Kerr. Image: National Gallery of Art

John Leeds Kerr

Kerr was born in 1780 near Annapolis, graduated from St. John’s College in 1795, and was admitted to the Maryland bar in 1801. He moved to Easton and practiced law there. He served as deputy state’s attorney for Talbot County from 1806 until 1810.

After commanding a company of militia during the War of 1812, in 1817 he was appointed as Maryland’s agent to press claims against the federal government that grew out of that war. Kerr was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1824 and served there until 1829. He was reelected to Congress in 1830 and served until 1833.

Kerr served as a presidential elector on the Whig ticket in 1840. He was elected as a Whig to the U.S. Senate in 1841 to complete the term of John S. Spence (also an Eastern Shore enslaver), who died in office. He served in the Senate from 1841 to 1843. Kerr died in Easton in 1844 and is interred in the Bozman family cemetery at “Bellville,” near Oxford Neck in Talbot County.

In 1820, Kerr owned six enslaved persons: one boy; two men; one girl; and two women. Twenty years later, the number of people he held in bondage had increased to 25: eight boys and young men; five men; one older man; six girls and young women; and five women.

Edward Lloyd

Edward Lloyd, another citizen of Talbot County and the owner of Wye House plantation, owned by far the largest number of enslaved people in this group. He served as the 13th governor of Maryland and was a U.S. senator and a member of the House of Representatives.

He was also the owner of the most famous man who escaped slavery on the Eastern Shore — Frederick Douglass — who achieved national and international fame. Lloyd held 30 people in slavery in 1790, but by 1830, four years before his death, there were 440 men, women, and children in his possession.

We can see a few commonalities among the enslavers on the mid-Shore. All were major landowners, all practiced law in their communities, and all had the wealth and the time to devote themselves to careers in politics, while their households and lands were cared for by the enslaved.

Sources:

"More than 1700 congressmen once enslaved Black people. This is who they were, and how they shaped the nation." Julie Zauzmer Weil, Adrian Blanco, and Leo Dominguez. Washington Post, Jan. 10, 2022.

Ancestry

https://www.ancestry.com/search/

Wikipedia, Charles Goldsborough

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Goldsborough

Wikipedia, Thomas Holliday Hicks

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Holliday_Hicks

Wikipedia, William Hindman

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Hindman

Wikipedia, John Leeds Kerr

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Leeds_Kerr

Wikipedia, Edward Lloyd

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Lloyd_(Governor_of_Maryland)

Wikipedia, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Life_and_Times_of_Frederick_Douglass_(1892)_p71.png

A native of Wicomico County, George Shivers holds a doctorate from the University of Maryland and taught in the Foreign Language Dept. of Washington College for 38 years before retiring in 2007. He is also very interested in the history and culture of the Eastern Shore, African American history in particular.

Common Sense for the Eastern Shore