Quiz: How Much do You Know About Plastic Recycling?

Take the quiz: how much do you know about plastic recycling?

World-wide, 300 million tons of plastic are produced each year, half of which is for single-use items.

Most plastic pollution comes from single-use plastics, including bottles, wrappers, straws, and bags — items that are expected to be discarded immediately after use. Single-use plastics accumulate in landfills, pollute the ocean, pile up on coastlines, damage habitats, and harm marine life. We’ve all seen photos of dead whales, fish, turtles, and seabirds with guts full of plastic trash they thought was food. That’s our garbage.

Most plastic waste does not get recycled. A recent study found that only 9% of all plastic waste ever produced has been recycled. Another study concluded that, in 2016, only 15% of plastic was recycled.

Eleven million metric tons of plastic “leaked” into the ocean in 2016, roughly the equivalent of dumping a garbage truck full of plastic into the ocean every minute. Unless we change the way we’re handling plastic waste, the annual flow of plastic into the ocean will nearly triple, to 29 million metric tons, by 2040.

But plastic bottles and bags littering the shores are not the only problem created when plastics enter our waters. Microplastics are created when larger pieces of plastic degrade into smaller pieces (less than 5mm long — about the size of a sesame seed). It is easy to see this phenomenon by walking along a beach where plastic has washed up. (Microplastics are also created from industrial pellets and tire wear and tear.)

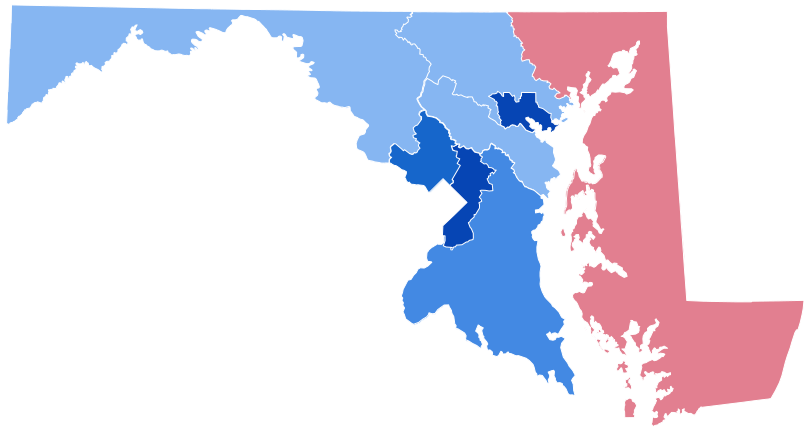

Microplastics have been found in the water we drink — both tap and bottled — and the food we eat. Multiple studies have found microplastics in a large proportion and wide variety of marine animals in the Chesapeake Bay and the ocean. It’s impossible for us not to ingest microplastics.

The complete picture of the long-term health implications of ingesting microplastics and the chemicals they contain is not known, but researchers suspect negative impacts on our gut biome, and inflammation, immunity, hormonal imbalances, reproductive problems like infertility, cancer, and threats to our overall health. More study is needed.

Experts agree that there’s no single or simple solution to this problem of plastic pollution. The mantra Reduce, Reuse, Recycle is a road map for a solution, but emphasis among the three tactics needs to be shifted away from recycling (which was always intended as a last resort — notice it’s listed last).

The big single-use plastic producers — bottle makers and plastic bag producers — take the position that it’s up to the consumer to deal with all their plastic waste, even as they produce more and more of it. They claim that consumers demand convenience, that our throw-away culture of single-use plastic fills that need, and that consumers must therefore assume the responsibility of recycling. However, we know that only a small percentage of plastic is ever recycled, and many communities lack the capacity to recycle even 25% of plastic waste. So recycling alone is not the answer.

Plastic producers and companies that serve single-use plastics to their customers need to take more responsibility for the waste they generate. And some have, for example, offering paper straws instead of plastic.

But because most have not done so on their own initiative, legislation is needed. Many communities have banned single-use plastic bags, or require that shoppers purchase them; both strategies have been shown to greatly reduce the amount of plastic waste in those communities. Other communities have enacted bottle bills to encourage the use of refillable bottles over disposable plastic. Oceana, an organization working exclusively to protect and restore the oceans, estimates that just a 10% increase in the share of soft drink beverages sold in refillable bottles could decrease marine plastic pollution by 22%.

Scientists, governments, and planners are proposing innovative solutions. California (often in the forefront of environmental protection legislation) came close last year to passing the Circular Economy and Plastic Pollution Reduction Act — legislation that would set goals to reduce waste from single-use packaging and products and ensure the remaining items are effectively reusable or recycled and composted. The legislation will be a referendum question in 2022. The System Change Scenario, modeled by The Pew Trusts, proposes a method by which plastic production and consumption would be reduced through a combination of elimination, the expansion of consumer reuse options, and new delivery models.

Plastic pollution is a big problem that requires action on many fronts, not just recycling.

So, how much do you know about plastic recycling?

Take the quiz and find out.

Jan Plotczyk spent 25 years as a survey and education statistician with the federal government, at the Census Bureau and the National Center for Education Statistics. She retired to Rock Hall.

Common Sense for the Eastern Shore