The Art of Teaching: Problem Solved

Classroom. Photo: Holly Dornak, via Pixabay

Students have so many questions to answer. How is an eagle’s nest constructed? How do I speak to legislators about topics that are important to my family? What are the functions of the lobes of the brain? What should we do with all that chicken poop? How does trajectory science work at the scene of the crime? How do I become a conscientious consumer of chocolate? What is sustainable farming? How does algebra solve my architectural dream? Why is the James Webb telescope using salt crystal lenses? With a few discount store items, some research and planning, students learn the answers and find passions.

Everything begins with a problem that needs a solution, and teaching is no exception. When a lesson begins with a problem that can be solved with multiple solutions, students feel safe to engage to solve it. The key to teaching children successfully is making sure you offer a question they want to answer.

Problem-based learning is nothing new but is often dismissed because of teacher preparation time, materials costs, classroom management, and fear of the instruction not meeting testing standards. It has truly earned an unfair reputation.

How does problem-based learning cover necessary content? Teaching is about students questioning rather than teachers lecturing. Students will find many engaging questions that cover all standardized questions that will be asked of students.

Despite skepticism, teachers can manage students who are working with a variety of potentially hazardous materials. Students appreciate materials and safety protocols when they know they will produce something they desire or need. If the teacher is willing to build relationships, to remind, and to reinforce, students will respect and value property and safety.

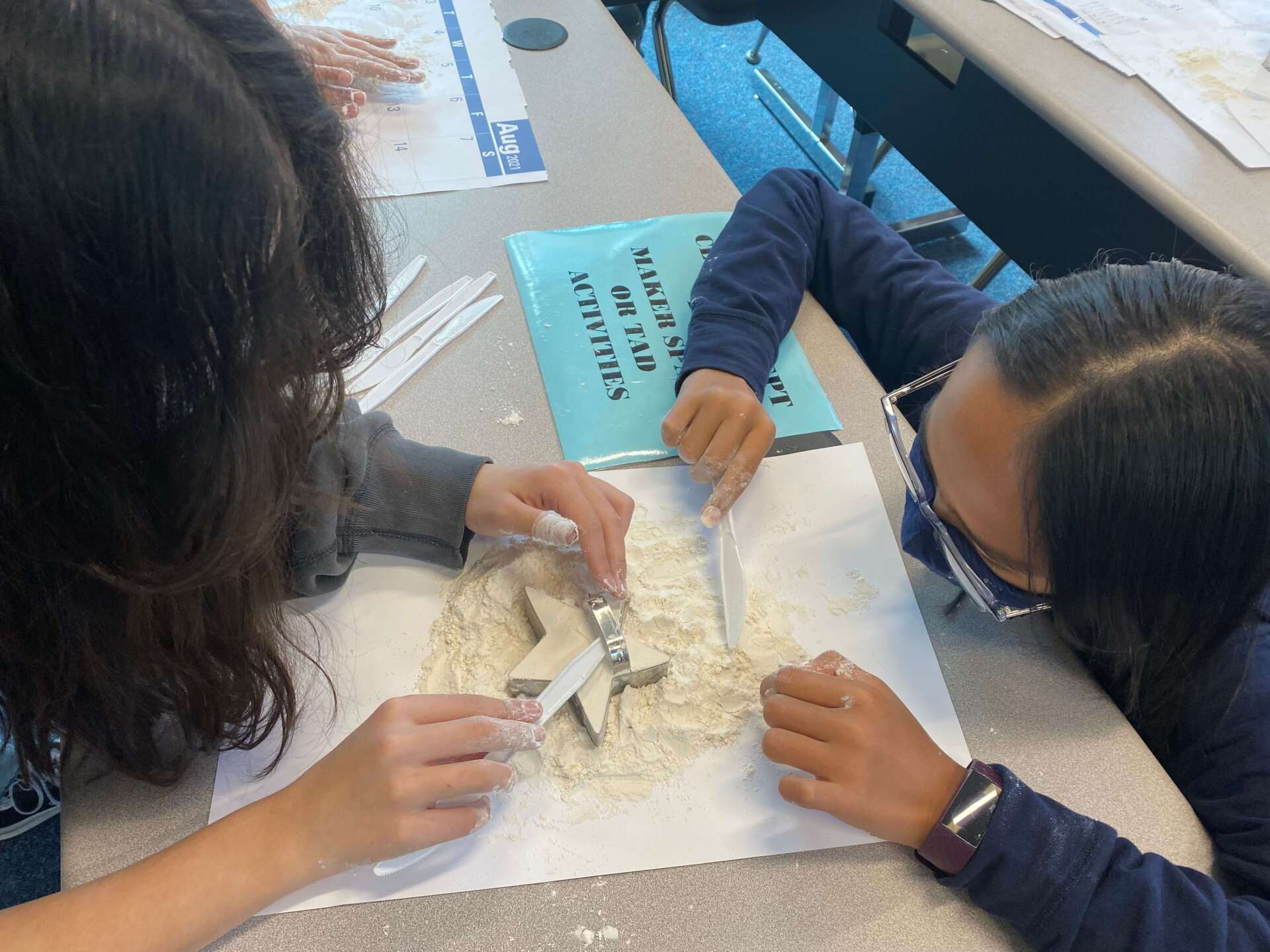

Materials are expensive; however, cost is an obstacle that can be overcome. Many materials for problem-based learning reside in our landfills. Recycling is a key concept of problem-based learning. Think of this as “trash to treasure” as most of these items can be repurposed to “simulate” an experience. A trip to any discount store or thrift shop opens a world of possibilities. The trick is to try to see an object for what it can represent instead of what it is. In my classroom, flour and cookie cutters become beryllium and sophisticated technology in a NASA laboratory. Another solution to maintaining a reasonable budget is to apply for grants. There are many grants available and by putting in some time to research options, teachers can often find additional funding sources that push beyond the typical school material budget. Organizations are more than willing to help and to enjoy the benefits of seeing the products of learning because students’ projects often solve a community need or problem.

Consider these examples of problems my students and I decided to tackle. Plants come with problems. But middle schoolers are rarely excited about plants. Plant problems involve construction, messes, splashing water, engineering principles, insects, and going outside. These problems do excite students.

This year we introduced hydroponic gardening into our classroom.

Phase 1: The problem.

How can thriving plants be grown indoors without soil? Students are presented with a variety of materials scattered about to solve the problem. With laptops ready, students perform some basic research and are quick to answer: “hydroponics”.

Phase 2: Construction and engineering.

The hydroponic process involves water, electricity, construction, power tools, and a lot of safety protocols. Students must be actively working and critically thinking. At this point, the teacher has moved to a role as a facilitator and, with a lot of patience, will guide students through the rest of this process.

Phase 3: Pose more questions.

“How can I make my parents happy by eating a healthy salad and still like the taste?” The plant selection process and research are easy when asking this question. The students are provided a list of plants which grow hydroponically and begin researching. The motivation is not only a better salad but knowing that they will grow the plants. The teaching is now about student ownership.

Phase 4: Failure.

Mites … a lot of mites! In our case, students are growing the plants successfully until they are not. Mites mean research, microscopes, and more questions. How do we stop the mites, save our plants, and keep our salad healthy? Do different kinds of mites respond differently to treatment methods? How do we treat our plants naturally? The teacher is again a facilitator, and we are covering a lot of content and life skills: biology, entomology, chemistry, botany, budgeting, time management, collaboration, critical thinking, and most importantly, failure. The teacher is now the cheerleader, and the students take on the role of superheroes and heroines.

Phase 5: Data.

Students collect data from the plants and treatment methods to protect their investment. Students have now become science stakeholders.

Phase 6: Harvest.

There is something magical about watching kids eating a vegetable and liking it because they grew it, researched it, raised it, fixed it, and loved it. The teacher's job now is to resume the role of teacher and remind them of all they have learned. The students can recall the entire process and take pride in their learning. Students were having so much fun that they forgot this is school.

This is teaching and learning in the truest sense. It is not boring, unrewarding, miserable, jaded, or cynical. Problem-based teaching and learning is messy, fun, complex, simple, rewarding, sustainable, productive, and hopeful.

April Todd, a graduate of Washington College and Salisbury University, is a problem-based teacher with Wicomico County Public Schools. April instructs TAD (Thinking and Doing) for grades 6-8 at Salisbury, Pittsville, and Mardela Middle Schools. In 2008, she was named Maryland Teacher of the Year, and she was a 2021 Maryland Educators of Gifted Students Teacher of the Year. This is her 24th year in education. April plans to learn and laugh with her students for many years to come.

Common Sense for the Eastern Shore