The Electoral College, Part 1: What Is It?

Sherwin Markman • May 26, 2020

Ah, yes, here we go again, four years later, facing what our president admires and the Democrats decry: the Electoral College. Thus, as Americans — as good citizens — it behooves us to take still another look at it, swallow whatever joy or dismay we may feel, and deal with it as best we can.

I will attempt to set down on paper here in four short (relatively) articles, an overview that will cover, in turn: What is this Electoral College of ours? How did it happen to come about? What has it done to us? Ought it to be changed and, if so, how?

So, then, what is this Electoral College?

Well, first of all, it is no “college” at all. It is, instead, a group of people appointed state by state in whatever manner each state legislature directs, who, in turn, determine, by majority vote, the person who shall be the president of the United States.

Specifically, what has become known as the Electoral College, was created by Article II, Section I of our Constitution, as modified and changed by Amendment XII (ratified on June 15, 1804), Amendment XX (ratified on January 23, 1933), and Amendment XXIII (ratified on March 29, 1961). Putting this all together, this is what we have now:

1. Each state shall “appoint”;

2. In such manner as its state legislature directs;

3. A number of “electors”;

4. Equal to the whole number of its representatives in Congress plus its two senators (Thus, Maryland, for example, now has 10 electoral votes — eight members of the House plus its two senators). In addition, the District of Columbia has been granted the electoral votes of the least populous state (three);

5. And the electors shall meet in their own states at a uniform time as set by Congress;

6. Where they shall cast their ballots separately for president and vice president; and

7. The candidates who receive a majority of those votes shall become president and vice president, respectively.

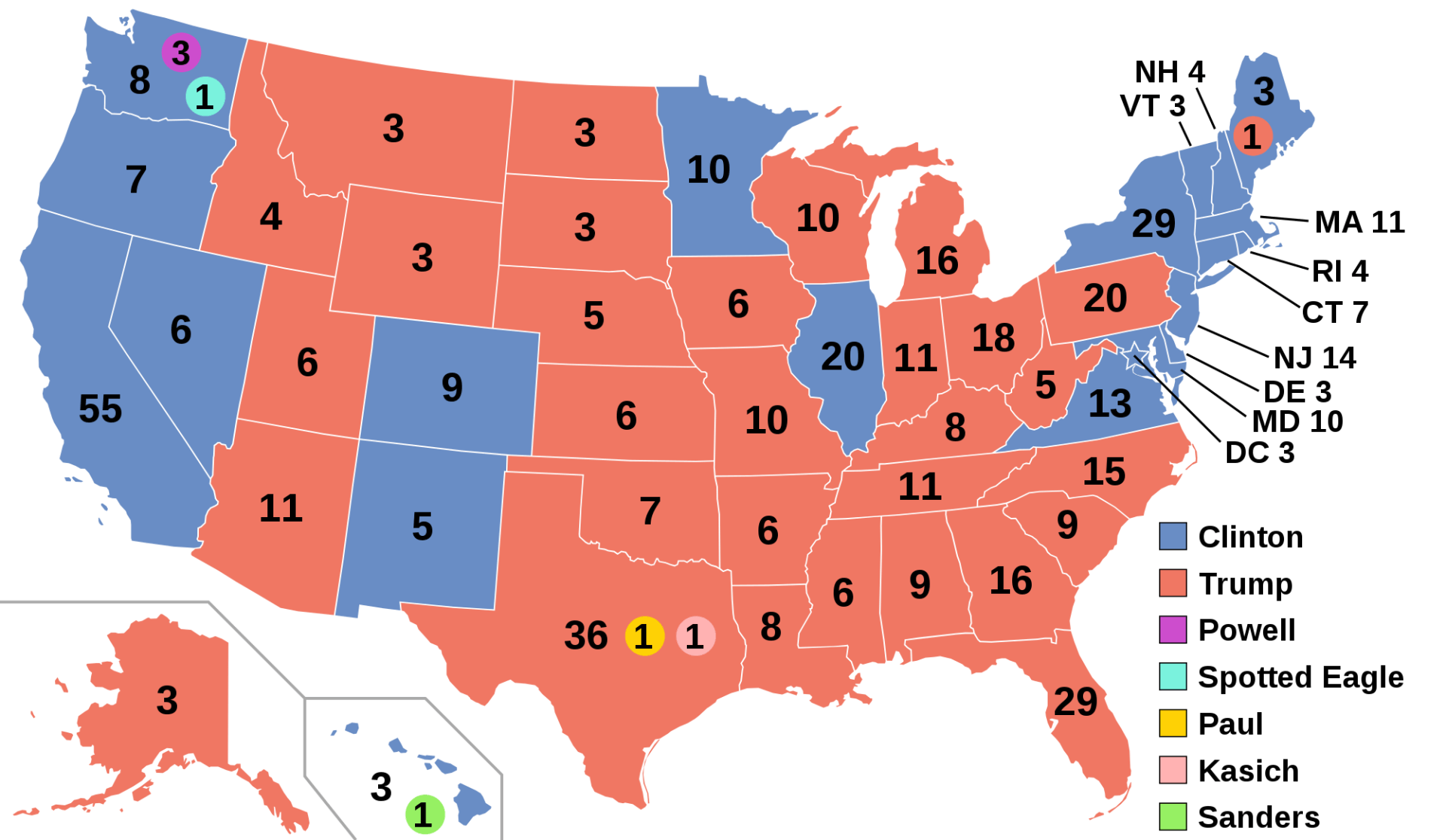

There are now 538 Electors, a number reached by adding 435 voting members of the House, plus the 100 senators, plus the three votes granted to the District of Columbia. Thus, it takes at least a 270 electoral vote majority to elect a president.

Even though there is no requirement to do so, every state provides that its electors are to be selected by popular vote, and, except for Maine and Nebraska (which apportion their votes), every state has decreed that all of its electors shall vote as the winner of its popular vote decides; i.e., winner takes all.

And so it is that under our electoral system, the idea that all American citizens have the same voting power utterly disappears. Thus, California, with its 55 electoral votes, has 60 times the population of Vermont, with its three electoral votes. Therefore, each Vermont voter’s presidential vote is worth three and a half times that of each California voter. The inescapable truth is that all citizens living in large population states are severely penalized in the selection of our president.

The disparity in voting equality is far worse if an election results in no candidate winning a majority of the electoral votes. In that eventuality (which could — and has on occasion — come about when more than two viable candidates are in the race), our Constitution provides that the presidential selection is sent to the House of Representatives, which is to vote among the top three electoral vote candidates. But the voting in the House is unique: It is not congressman by congressman, but, instead, it is state by state. Each of our 50 states gets one vote, and that vote is determined by a majority of its congressman. If the state’s congressional delegation vote ends up in a tie, that state does not vote. The winner is the candidate who wins the votes of 26 states.

Under this system, again using Vermont and California as examples, each state has an equal one vote voice in the election, and thus the weight of a Vermont citizen’s presidential vote becomes 60 times that of a citizen of California. To put all of it into perspective, 26 states representing less than 16 percent of our nation’s population, could elect our president.

Under our current system, the failure of any presidential candidate to receive a majority of the electoral votes will also result in a similar electoral failure by any vice-presidential candidate. However, unlike the presidential selection, the Constitution provides that, in that case, the selection of the vice president will be made between the two top candidates by the Senate, voting as it normally does.

None other than Thomas Jefferson, when contemplating this system in 1823, stated:

“I have ever considered the constitutional mode of election ultimately by states as the most dangerous blot on our Constitution, and one which will someday hit.”

And so we come to the question: How in the world did this all come about? That will be addressed in my next article.

Sherwin Markman, a graduate of the Yale Law School, lives in Rock Hall, Maryland. He served as an assistant to President Lyndon Johnson, after which he was a trial lawyer in Washington, D.C. He has published several books, including one dealing with the Electoral College. He has also taught and lectured about the American political system.

Common Sense for the Eastern Shore

Voters in Hurlock have delivered sweeping changes in this year’s municipal election, as Republican and GOP-aligned candidates won key races there. The results mark a setback for Democrats and a significant political shift in a community that has historically leaned Democratic in state and federal contests. The outcome underscores how local organizing and turnout strategies can have an outsized impact in small-town elections. Analysts also suggest that long-term party engagement in municipal contests could shape voter alignment in future county and state races. Political analysts warn that ignoring municipal elections and ceding them to the GOP could hurt the Maryland Democratic Party in statewide politics. Turnout increased by approximately 17% compared with the 2021 municipal election, reflecting heightened local interest in the mayoral and council races. Incumbent Mayor Charles Cephas, a Democrat, was soundly defeated by At-Large Councilmember Earl Murphy, who won with roughly 230 votes to Cephas’s 144. In the At-Large Council race, Jeff Smith, an independent candidate backed by local Republicans, secured a 15-point win over Cheyenne Chase. In District 2, Councilmember Bonnie Franz, a Republican, was re-elected by 40 percentage points over challenger Zia Ashraf, who previously served on the Dorchester Democratic Central Committee. The only Democrat to retain a seat on the council was David Higgins, who was unopposed. The Maryland Republican Party invested resources and campaign attention in the Hurlock race, highlighting it on statewide social media and dispatching party officials, including Maryland GOP Chair Nicole Beus Harris, to campaign. Local Democrats emphasized support for Mayor Cephas through the Dorchester County Democratic Central Committee, but the Maryland Democratic Party did not appear to participate directly.

In what political observers are calling a clear break from Maryland’s moderate Republican establishment, Wicomico County Executive Julie Giordano chose former Gov. Bob Ehrlich — not former Gov. Larry Hogan — as the guest of honor at her re-election fundraiser in late October. Billed as Giordano’s annual Harvest Party, her event drew conservative activists from across the lower Eastern Shore and featured Ehrlich as keynote speaker. This was immediately read by insiders as a signal that Giordano will embrace the party’s right-wing base ahead of 2026, distancing herself from Hogan’s more centrist, bipartisan image. “Bringing in Bob Ehrlich instead of Larry Hogan wasn’t accidental,” one longtime Republican strategist said. “It shows Giordano wants to plant her flag with the MAGA-aligned wing of the party, the same voters who now dominate Maryland’s Republican primary base.” Hogan, who has hinted at another run for governor, was notably absent from this year’s Tawes Crab and Clam Bake in Somerset County, a high-profile gathering long considered essential for statewide contenders. Coupled with Giordano’s public alignment with Ehrlich, Hogan’s absence has fueled speculation that his influence within Maryland’s GOP is slipping. Those doubts were amplified by new polling data. A statewide survey commissioned by the Baltimore Banner found Gov. Wes Moore (D) leading Hogan 45% to 37% in a hypothetical 2026 matchup, with 14% undecided. The poll, conducted by phone and web from Oct. 7–10 among more than 900 registered voters, carries a margin of error of 3.2 percentage points. The results suggest that while Hogan remains popular among moderates and independents, Moore continues to hold a firm advantage statewide, particularly among Democrats and younger voters. Giordano’s decision to align herself with Ehrlich rather than Hogan further illustrates the ideological divide defining Maryland Republicans heading into 2026. As the party drifts further to the right, analysts say Hogan’s brand of pragmatic centrism may no longer have a natural home in today’s GOP. For now, Ehrlich’s appearance in Salisbury is being seen as a symbolic moment, one that cements Giordano’s status as a leading figure in the state’s Trump-aligned movement and underscores how quickly the political winds have shifted. For Hogan, once seen as the Republican best positioned to reclaim the governor’s office, that shift may mark the end of an era.

Can Maryland create a new congressional map that will flip the state’s sole Republican district to the Democrats? Gov. Wes Moore has created a Governor's Redistricting Advisory Commission to consider mid-cycle redistricting and Maryland has jumped into the redistricting fray. The commission will conduct public hearings, solicit public feedback, and present recommendations to the governor and Maryland General Assembly. “My commitment has been clear from day one — we will explore every avenue possible to make sure Maryland has fair and representative maps,” said Moore. “And we also need to make sure that, if the president of the United States is putting his finger on the scale to try to manipulate elections because he knows that his policies cannot win in a ballot box, then it behooves each and every one of us to be able to keep all options on the table to ensure that the voters’ voices can actually be heard .” Moore’s commission is one of those options — a response to Trump’s call to Republican-led states to create more GOP House districts before the 2026 midterm elections. Three GOP states — Texas, Missouri, and North Carolina — have completed a Trump gerrymander for a gain of seven seats and three more states — Indiana, Utah, and Ohio — could create new maps with a total of four additional Republican seats. That would make 11, should they withstand challenges. Democratic-led states made a lot of noise at first about countering these GOP efforts, but only California and Virginia have campaigns for new maps underway. California wants to flip five seats and Virginia hopes for up to four. Optimistically, that could add up to as many as nine. Maryland’s goal would be to add one Democratic seat. Other states on both sides could soon follow, in some cases taking advantage of existing redistricting deadlines or ongoing litigation. Maryland State Senate President Bill Ferguson (D-Balto City) is not in favor of mid-cycle redistricting, calling it too dicey. “Simply put, it is too risky and jeopardizes Maryland’s ability to fight against the radical Trump administration. At a time where every seat in Congress matters, the potential for ceding yet another one to Republicans here in Maryland is simply too great,” Ferguson wrote in a letter to Senate Democrats. Rep. Andrew P. Harris (R-MD01), whose district would be targeted by redistricting, called the effort "the most partisan thing you could do." He whined, “It just wouldn’t be fair.” Harris warned that any redistricting could backfire on the Democrats. “We will take this to court, it will go as high as necessary, and in the end, a judge could draw a map that actually has two or three Republican congressmen,” Harris said. “I’d caution the Democrats, be careful what you wish for.” Harris and his wife, Maryland GOP Chair Nicole Beus Harris, have perhaps already worked out a strategy. The Governor’s Redistricting Advisory Commission, last constituted by Gov. Martin O’Malley in 2011, will begin its work this month. The five-member commission includes: Chair: Senator Angela Alsobrooks Senate President Bill Ferguson or designee Speaker Adrienne A. Jones or designee Former Attorney General Brian Frosh Cumberland Mayor Ray Morriss “We have a president that treats our democracy with utter contempt. We have a Republican party that is trying to rig the rules in response to their terrible polling,” said Sen. Alsobrooks. “Let me be clear: Maryland deserves a fair map that represents the will of the people. That’s why I’m proud to chair this commission. Our democracy depends on all of us standing up in this moment.” Will Maryland’s First District finally be competitive? Can we at long last replace “AWOL Andy” Harris? Stay tuned…. Jan Plotczyk spent 25 years as a survey and education statistician with the federal government, at the Census Bureau and the National Center for Education Statistics. She retired to Rock Hall.

In strong numbers, local residents turned out last month for a community information session on offshore wind hosted by the Alliance for Offshore Wind at the Ocean Pines library. The forum heard from industry experts, environmental advocates, and labor leaders to discuss how offshore wind projects can support jobs, clean energy, and coastal resilience along Maryland’s Eastern Shore. Featured were Sam Saluto of Oceantic, Jim Strong of the United Steelworkers, Ron Larsen of Sea Ink Solutions, and Jim Brown of the Audubon Society, all of whom emphasized the long-term environmental and economic benefits of wind development off Maryland’s coast. Speakers outlined how the project, once completed, is expected to create hundreds of high-paying jobs, generate clean power for tens of thousands of homes, and reduce reliance on fossil fuels that cause pollution and coastal erosion. “The potential here is extraordinary,” said Saluto, highlighting Oceantic’s ongoing work to ensure safety and sustainability standards remain at the highest level. “We’re not just talking about wind turbines. We’re talking about revitalizing local economies and protecting the Shore’s way of life.” Union representative Jim Strong echoed that sentiment, noting that Maryland’s labor community sees offshore wind as a chance to rebuild domestic manufacturing capacity while giving workers access to strong wages and long-term stability. Environmental voices, including Jim Brown of the Audubon Society, focused on how properly sited wind projects can reduce carbon emissions while coexisting with marine wildlife and migratory bird patterns. While most of the evening centered on data and community questions, the event briefly turned tense when Ocean City Mayor Rick Meehan, who is leading a lawsuit challenging Maryland’s offshore wind plans, attempted to question the panel. The mayor appeared to lose his train of thought mid-sentence and later cast doubt on the reality of climate change, drawing visible concern from several attendees. Meehan, a New Yorker who moved to Ocean City in 1971 and has held public office since 1985, has become one of the region’s most vocal opponents of offshore wind. His critics argue the lawsuit represents an effort to stall progress rather than engage with the facts presented by energy, labor, and environmental experts. Despite the brief exchange, the overall tone of the evening was forward-looking. Residents lingered after the formal discussion to review informational materials, speak with industry representatives, and learn about opportunities for community involvement. For many, the message was clear: Maryland’s transition to clean energy is not only feasible, it’s already underway, and the Eastern Shore stands to benefit.

Sparking alarm among housing advocates, social workers, and residents, Salisbury Mayor Randy Taylor has announced plans to gut Salisbury’s nationally recognized Housing First program, signaling a break from years of bipartisan progress on homelessness. Created in 2017 under then-Mayor Jacob Day, the initiative was designed around a simple but powerful principle: that stable, permanent housing must come first before residents can address problems with employment, health, or recovery. The program was designed to provide supportive housing for Salisbury’s most vulnerable residents — a model backed by decades of national data showing it reduces homelessness, saves taxpayer dollars, and lowers strain on emergency services. But under Taylor’s leadership, that vision appears to be ending. In a letter to residents, the City of Salisbury announced that the Housing First program will be shut down in 2027, in effect dismantling one of the city’s long-term programs to prevent homelessness. Taylor says he plans to “rebrand” the program as a temporary “gateway to supportive housing,” shifting focus away from permanent stability and toward short-term turnover. “We’re trying to help more people with the same amount of dollars,” Taylor said. Critics call that reasoning deeply flawed, and dangerous. Former Mayor Jacob Day, who helped launch the initiative, says that Housing First was always intended to be permanent supportive housing, not a revolving door. National studies show that when cities replace permanent housing programs with short-term placements, people end up right back on the streets, and that costs taxpayers more in emergency medical care, policing, and crisis intervention. Local advocates warn that Taylor’s move will undo years of progress. “This isn’t just a policy shift, it’s a step backward,” one social service worker said. “Housing First works because it’s humane and cost-effective. This administration is turning it into a revolving door to nowhere.” Even some community partners who agree the program needs better oversight say that Taylor is missing the point. Anthony Dickerson, Executive Director of Salisbury’s Christian Shelter, said the city should be reforming and strengthening its approach, not abandoning its foundation. Under Taylor’s proposal, participants could be limited to one or two years in housing before being pushed out, whether or not they’re ready. Advocates fear this change could push vulnerable residents back into instability, undoing the progress the city was once praised for. While Taylor touts his plan as a way to “help more people,” critics say it reflects a troubling pattern in his administration: cutting programs that work. For years, Salisbury’s Housing First initiative has symbolized compassion and evidence-based leadership and has stood as a rare example of a small city tackling homelessness with dignity and results. Now, as Taylor moves to end it, residents and advocates are asking a simple question: Why would a mayor tear down one of Salisbury’s most successful programs for helping people rebuild their lives?

On the first Monday of October, the Supreme Court began a new term, Term 2025 as it is officially called. The day also marked John Roberts’ 20 years as Chief Justice of what history will clearly record as the Roberts Court. Twenty years is a long time but at this point, Roberts is only the fourth longest serving Chief Justice in our history. John Marshall, the fourth and longest, served for 34 years, 152 days (1801–35). Roger Brooke Taney, served for 28 years, 198 days (1836–64). Melville Fuller, served 21 years, 269 days (1888 to 1910). John Roberts was originally nominated by George W. Bush to fill the seat held by the retiring Sandra Day O’Connor but, upon the unexpected death of William Rehnquist, Bush instead nominated Roberts to serve as Chief Justice. His nomination was greeted by enthusiasm and high hopes in many quarters. He was young, articulate, personable, and highly qualified, having had an impressive academic record, experience in the Reagan administration and the private bar, and service on the federal D.C. Court of Appeals for two years. His “balls and strikes” comment at his confirmation hearing struck many as suggesting judicial independence. He sounded as well very much like an institutionalist, having said at an early interview that “it would be good to have a commitment on the part of the Court to act as a Court.” Whatever else might be said 20 years later about the tenure of John Roberts as Chief Judge, the Supreme Court is no doubt much less popular and much more divisive today than it was on September 29, 2005, when he was sworn in as the 17th Chief Justice by Justice John Paul Stevens, then the Court’s most senior associate justice, and witnessed by his sponsor, George W. Bush. Gallup’s polling data shows popular support for the Court now at the lowest levels since they started measuring it. In July 2025, a Gallup poll found that, for the first time in the past quarter-century, fewer than 40% of Americans approved of the Supreme Court’s performance. According to Gallup, one major reason that approval of the Supreme Court has been lower is that its ratings have become increasingly split along party lines — the current 65-point gap in Republican (79%) and Democratic (14%) approval of the court is the largest ever. The legal scholar Rogers Smith wrote in The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science in June, “Roberts’s tenure as Chief Justice has led to the opposite of what he has said he seeks to achieve. The American public now respects the Court less than ever and sees it as more political than ever.” These results signify more than simply a popularity poll because a Court without broad public support is a Court that will not have the same public respect upon which their most important decisions have historically depended. And, whatever the reasons for this development, it has happened on John Roberts’s watch. There is no better example of the current divisiveness on the Court than the remarkable string of “emergency” rulings on the Court’s so-called shadow docket since January 20. The extent of ideological and partisan differences has been sharp and extreme. The conservative majority’s votes have frequently been unexplained, leaving lower court judges to have to puzzle the decision’s meaning and leaving the public to suspect partisan influences. And the results of these shadow docket rulings have had enormous, sometimes catastrophic, consequences: Removing noncitizens to countries to which they had no ties or faced inhumane conditions Disqualifying transgender service members Firing probationary federal workers and independent agency heads Ending entire governmental departments and agencies without congressional approval Allowing the impounding of foreign aid funds appropriated by Congress Releasing reams of personal data to the Department of Government Efficiency Allowing immigration raids in California based on racial and ethnic profiling John Roberts has written many Supreme Court opinions in his 20 years as Chief Justice. At the 20-year mark, the most important, to the nation and to his legacy, will likely be his opinion in the Trump immunity case, which changed the balance of power among the branches of government, tipping heavily in the direction of presidential power. Trump v. United States (2024). In her dissent from his majority opinion in that case, Justice Sonia Sotomayor, joined by Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson, warned about the consequences of such a broad expansion of presidential power. “The Court effectively creates a law-free zone around the president,” upsetting the status quo that had existed since the nation’s founding and giving blanket permission for wrongdoing. “Let the president violate the law, let him exploit the trappings of his office for personal gain, let him use his official power for evil ends. In every use of official power, the president is now a king above the law.” Roberts claimed in his majority opinion that the “tone of chilling doom” in Sotomayor’s dissent was “wholly disproportionate” to what the ruling meant. However, Sotomayor’s words have proved prescient: the breadth of power that Trump and his administration have asserted in the months since he was sworn in for his second term has made plain how boundlessly they now interpret the reach of the presidency in the wake of the Roberts opinion. Despite the early “balls and strikes” comment, the assessment of John Roberts’ long term judicial record suggests something different as seen by several distinguished legal commentators from significantly different perspectives. As summarized by Lincoln Caplan, a senior research scholar at Yale Law School, in a new retrospective article on Robert’s 20-year tenure, “From his arrival on the Court until now, his leadership, votes, and opinions have mainly helped move the law and the nation far to the right. An analysis prepared by the political scientists Lee Epstein, Andrew Martin, and Kevin Quinn found that in major cases, the Roberts Court’s record is the most conservative of any Supreme Court in roughly a century.” “What Trump Means for John Roberts's Legacy,” Harvard Magazine , October 8, 2025. Steve Vladeck, Georgetown Law Center professor and a regularly incisive Court commentator, characterized the 20-year Roberts’ Court as follows: “The ensuing 20 years has featured a Court deciding quite a lot more than necessary — inserting itself into hot-button social issues earlier than necessary (if it was necessary at all); moving an array of previously settled statutory and constitutional understandings sharply to the right; and, over the past decade especially, running roughshod over all kinds of procedural norms that previously served to moderate many of the justices’ more extreme impulses.” “The Roberts Court Turns Twenty,” One First , September 29, 2025. In another remarkable new article by a widely respected conservative originalist, similar concerns about the present Court have very recently been expressed. Caleb Nelson, who teaches at the University of Virginia and is a former law clerk to Justice Clarence Thomas, has written that the text of the Constitution and the historical evidence surrounding it in fact grant Congress broad authority to shape the executive branch, including by putting limits on the president’s power to fire people. “Must Administrative Officers Serve at the President’s Pleasure?” Democracy Project, NYU LAW , September 29, 2025. When the First Congress confronted similar ambiguities in the meaning of the Constitution, asserts Nelson, “more than one member warned against interpreting the Constitution in the expectation that all presidents would have the sterling character of George Washington.” Nelson continues, “The current Supreme Court may likewise see itself as interpreting the Constitution for the ages, and perhaps some of the Justices take comfort in the idea that future presidents will not all have the character of Donald Trump. But the future is not guaranteed; a president bent on vengeful, destructive, and lawless behavior can do lasting damage to our norms and institutions.” John Christie was for many years a senior partner in a large Washington, D.C. law firm. He specialized in anti-trust litigation and developed a keen interest in the U.S. Supreme Court about which he lectures and writes.