The Legacy of James Taylor, Chestertown, Md.

On May 12, 1892, a Kent County farmer’s daughter was assaulted in the kitchen of the family’s farm. James Taylor, a laborer on that farm, was accused of the crime. Mr. Taylor was a 23-year-old Black man.

Two days later, a mob of masked men dragged Mr. Taylor from the county jail, which was located next door to the courthouse in Chestertown. The newspaper reported that a crowd of 500 witnessed these men dragging Taylor to a small maple tree on the other side of Cross Street where they hanged him. Even though some of the lynchers had met with town officials the day before to discuss their intentions and there were 500 eyewitnesses, no one reportedly knew any of the men involved in the lynching.

James Taylor never had a chance to stand trial for his alleged crime; the presumption of innocence followed him to the grave. James Taylor maintained his innocence until the last hour of his life. When a Baltimore Sun reporter asked him if he was guilty, he replied, “No, sir, I am an innocent man and I am not afraid to say so even while I am expecting to meet my God in a few minutes.” Mr. Taylor was buried in the pauper’s graveyard and that was the end of it. Until now.

After the Civil War, racial terror reigned across our country — and not just in the South. The Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) has documented 6,500 lynchings in the U.S. between 1865 and World War II. This includes 38 documented lynchings in Maryland. As EJI states, “The lynching of African Americans was terrorism, a widely supported campaign to enforce racial subordination and segregation.”

Uniquely in the United States, Maryland has acted to acknowledge, research, and work toward reconciliation for the lynchings that occurred in our state. The Maryland Lynching Truth and Reconciliation Law (HB 307) was unanimously passed by both houses of the legislature and was signed into law by Gov. Hogan in February 2019. This law authorizes a state commission to research cases of racially motivated lynchings and to hold public meetings and regional hearings where a lynching of an African American by a white mob was documented.

In response to HB 307, the James Taylor Justice Coalition (JTJC) was formed in July 2019. A special committee of Sumner Hall, Chestertown, its membership includes a diverse group of citizens, including several Sumner Hall board members. The JTJC is dedicated to educating our community about the injustice of James Taylor’s 1892 lynching and making the connection between racial terror lynchings of the past and convict leasing, peonage, mass incarceration, incidents of police brutality and discrimination of today. Taylor’s guilt or innocence of the crime for which he was accused is irrelevant to JTJC’s mission. Mr. Taylor was denied a fair trial and justice under the laws of our land.

To advance its mission, JTJC:

- installed an exhibit at the Historical Society of Kent County about James Taylor’s story and the implications it has for life in today’s Kent County;

- offered a virtual book club that discussed Sherrilyn Ifill’s acclaimed book, On the Courthouse Lawn;

- became an active member of the Maryland Lynching Memorial Project, and an implementing partner of the Maryland Lynching Truth and Reconciliation Commission;

- produced Justice Day 2021;

- conducted an essay contest, co-sponsored by EJI, at the Kent County High School which challenged students in grades 9 – 12 to reflect on the impact of racial and social injustice in their lives.

Upcoming Events

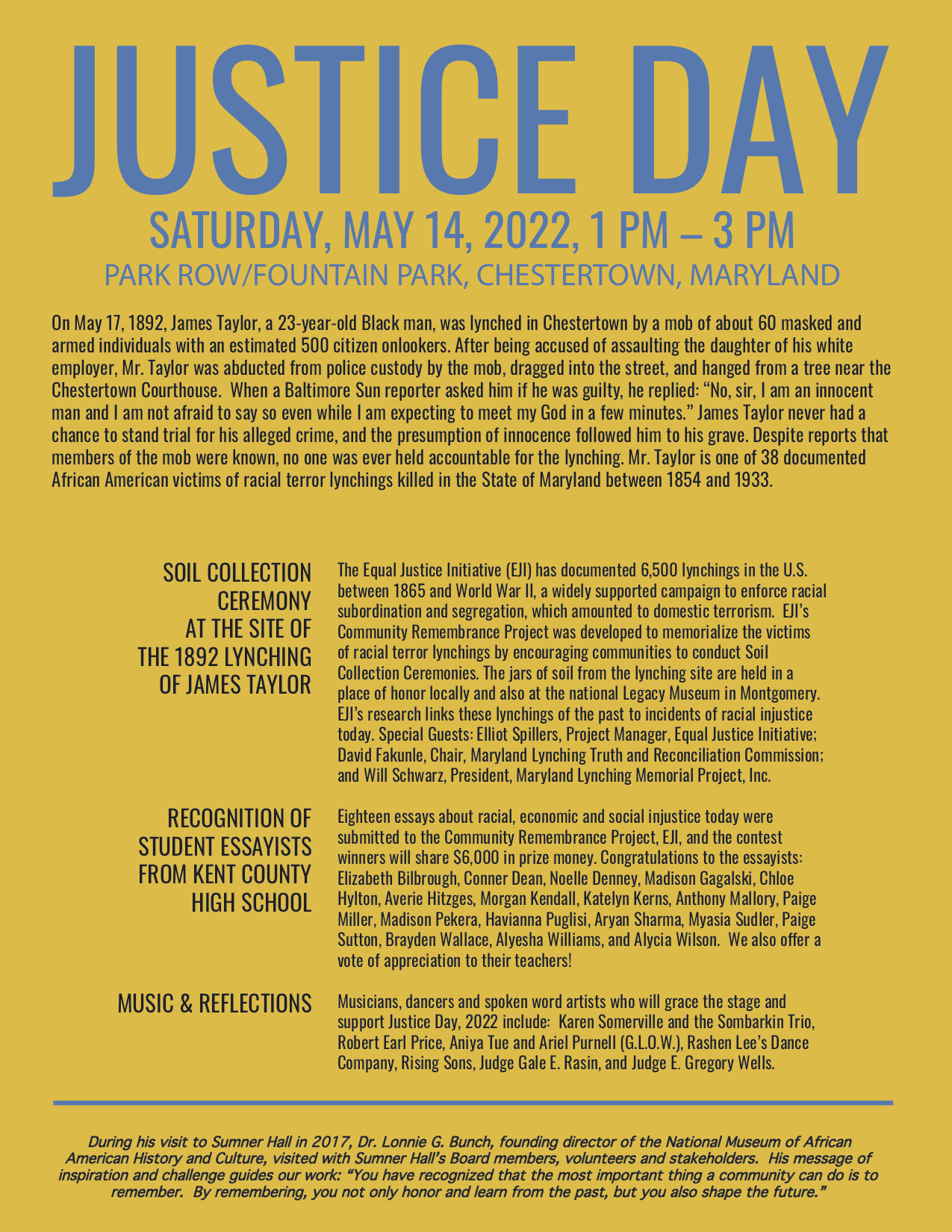

- Justice Day 2022. A second Justice Day will take place on May 14, from 1 to 3pm. This year the program will feature the announcement of the essay contest winners and the awarding of prize money by a representative of the Equal Justice Initiative. Excerpts of the winning essays will be read by the students. Justice Day will also include musical and spoken word performances. Finally, an EJI Community Remembrance Project Soil Collection ceremony will be conducted. The Community Soil Collection Project helps to publicly memorialize the traumatic era of racial terror by collecting soil from lynching sites in America. Glass containers will be filled with dirt from the site of the lynching of James Taylor. These will be displayed at Sumner Hall and at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama.

- Civil Rights Bus Tour. JTJC of Sumner Hall is partnering with Minary’s Dream Alliance to sponsor a six-day bus tour to significant civil rights sites in Alabama and Georgia on July 25-30, 2022. In addition to delivering the community remembrance jar of soil to EJI’s Legacy Museum, those on the tour will visit sites in Birmingham, Selma, Montgomery, and Atlanta, including the Civil Rights Institute, Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, Edmund Pettus Bridge, National Voting Rights Museum, Legacy Museum, National Memorial for Peace and Justice, Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Park, The King Center, Tomb of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Ebenezer Baptist Church. Tickets for this trip will be available to the public by May 20, 2022. Fundraising is currently underway to provide scholarships for 30 young people. To register for the trip or to contribute to the scholarship fund, go to Sumner Hall’s website.

- Maryland Lynching Truth and Reconciliation Commission Regional Hearing. The commission is holding hearings across the state of Maryland in every county where a lynching took place. The first one was held in Allegany County, and one is planned for Chestertown later in 2022. These hearings are designed to gather information about the events, hear from descendants of victims and perpetrators, and solicit input and ideas about reconciliation and healing. JTJC will assist the commission with this hearing.

The JTJC welcomes active participation by everyone in our community. If you are interested in learning more and helping with our work, please email us kentco.mdlp@gmail.com or info@sumnerhall.org.

In the words of a member of the Community Remembrance Project Coalition of Chattanooga, Tennessee, “There can be no reconciliation and healing without remembering the past.” The James Taylor Justice Coalition is committed to acknowledging the injustice of James Taylor’s murder and working toward equity for all citizens of Kent County.

Philip Dutton, born in Louisiana, is Co-Chair of the James Taylor Justice Coalition and a community activist and promotor of racial justice. He is also a talented keyboard artist and he and his band, The Alligators, perform often in the area with their brand of lively Zydeco music.

Common Sense for the Eastern Shore