The most cost-effective energy efficiency investments you can make — and how the new Inflation Reduction Act could help

Energy efficiency can save homeowners and renters hundreds of dollars a year, and the new Inflation Reduction Act includes a wealth of home improvement rebates and tax incentives to help Americans secure those saving.

It extends tax credits for installing energy-efficient windows, doors, insulation, water heaters, furnaces, air conditioners or heat pumps, as well as for home energy audits. It also offers rebates for low- and moderate-income households ’ efficiency improvements, up to US$14,000 per home.

Together, these incentives aim to cut energy costs for consumers who use them by $500 to $1,000 per year and reduce the nation’s climate-warming greenhouse gas emissions.

With so many options, what are the most cost-effective moves homeowners and renters can make?

My lab at UMass Lowell works on ways to improve sustainability in buildings and homes by finding cost-effective design solutions to decrease their energy demand and carbon footprint. There are two key ways to cut energy use: energy-efficient upgrades and behavior change. Each has clear winners.

Stop the leaks

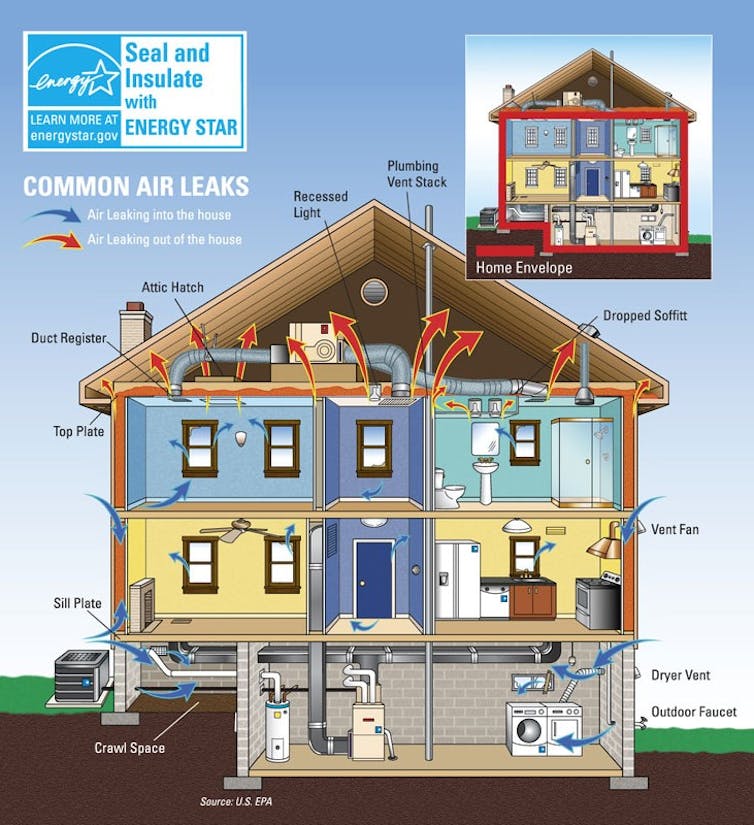

The biggest payoff for both saving money and reducing emissions is weatherizing the home to stop leaks. Losing cool air in summer and warm air in winter means heating and cooling systems run more, and they’re among the most energy-intensive systems in a home.

Gaps along the baseboard where the wall meets the floor and at windows, doors, pipes, fireplace dampers and electrical outlets are all prime spots for drafts. Fixing those leaks can cut a home’s entire energy use by about 6%, on average, by our estimates. And it’s cheap, since those fixes mostly involve caulk and weather stripping.

The Inflation Reduction Act offers homeowners a hand. It includes a $150 rebate to help pay for a home energy audit that can locate leaks.

While a professional audit can help, it isn’t essential – the Department of Energy website offers guidance for doing your own inspection.

Once you find the leaks, the act includes 30% tax credits with a maximum of $1,200 a year for basic weatherization work, plus rebates up to $1,600 for low- and moderate-income homeowners earning less than 150% of the local median.

Replace windows

Replacing windows is more expensive upfront but can save a lot of money on energy costs. Leaky windows and doors are responsible for 25% to 30% of residential heating and cooling costs , according to Department of Energy estimates.

Insulation can also reduce energy loss. But with the exception of older homes with poor insulation and homes facing extreme temperatures, it generally doesn’t have as high of a payoff in whole-house energy savings as weatherization or window replacement.

The Inflation Reduction Act includes up to $600 to help pay for window replacement and $250 to replace an exterior door.

Upgrade appliances, especially HVAC and dryers

Buildings cumulatively are responsible for about 40% of U.S. energy consumption and associated greenhouse gas emissions, and a significant share of that is in homes. Heating is typically the main energy use.

Among appliances, upgrading air conditioners and clothes dryers results in the largest environmental and cost benefits; however, HVAC systems – heating, ventilation and air conditioning – come with some of the highest upfront costs.

That includes energy-efficient electric heat pumps , which both heat and cool a home. The Inflation Reduction Act offers a 30% tax credit up to $2,000 available to anyone who purchases and installs a heat pump, in addition to rebates of up to $8,000 for low- and moderate-income households earning less than 150% of the local median income. Some high-efficiency wood-burning stoves also qualify.

The act also provides rebates for low- and moderate-income households for electric stoves of up to $840, heat-pump water heaters of up to $1,750 and heat-pump clothes dryers of up to $840.

Change your behavior in a few easy steps

You can also make a pretty big difference without federal incentives by changing your habits. My dad was energy-efficient before it was hip. His “hobby” was to turn off the lights. This action itself has been among the most cost-saving behavioral changes.

Just turning out the lights for an hour a day can save a home up to $65 per year. Replacing old lightbulbs with LED lighting also cuts energy use. They’re more expensive, but they save money on energy costs.

We found that a homeowner could save $265 per year and reduce emissions even more by adopting a few behavioral changes including unplugging appliances not being used, line-drying clothes, lowering the water heater temperature, setting the thermostat 1 degree warmer at night in summer or 1 degree cooler in winter, turning off lights for an hour a day, and going tech-free for an hour a day.

Some appliances are energy vampires – they draw electricity when plugged in even if you’re not using them. One study in Northern California found that plugged-in devices, such as TVs, cable boxes, computers and smart appliances, that weren’t being used were responsible for as much as 23% of electricity consumption in homes.

Start with a passive solar home

If you’re looking for a home to rent or buy, or even to build, you can make an even bigger difference by looking at how it’s built and powered.

Passive solar homes take advantage of local climate and site conditions, such as having lots of south-facing windows to capture solar energy during cool months to reduce home energy use as much as possible. Then they meet the remaining energy demand with on-site solar energy.

Studies show that for homeowners in cold climates, building a passive design home could cut their energy cost by 14% compared with an average home. That’s before taking solar panels into account.

The Inflation Reduction Act offers a 30% tax credit for rooftop solar and geothermal heating, plus accompanying battery storage, as well as incentives for community solar – larger solar systems owned by several homeowners. It also includes a $5,000 tax credit for developers to build homes to the Energy Department’s Zero Energy Ready Homes standard.

The entire energy and climate package – including incentives for utility-scale renewable energy, carbon capture and electric vehicles – could have a big impact for homeowners’ energy costs and the climate. According to several estimates

, it has the potential to reduce U.S. carbon emissions by about 40%

by the end of this decade.![]()

Jasmina Burek , Assistant Professor of Engineering, UMass Lowell

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Common Sense for the Eastern Shore