U.S. Deems Migrant Seafood Workers ‘Essential’ But Limits Their Covid-19 Protections

Lindy’s Seafood Inc., the wholesale crab and oyster company in Maryland that hired the workers, paid for their cross-country trip. The company put them to work the day after they arrived without quarantining or covid-19 test results. Those safeguards are not required under state or federal law.

Migrant seafood-processing workers face heightened risks of catching covid-19. Classified as essential workers, they are permitted to continue working even if they come in contact with the coronavirus. Within a week, the Lindy’s workers were informed that several had tested positive for the disease.

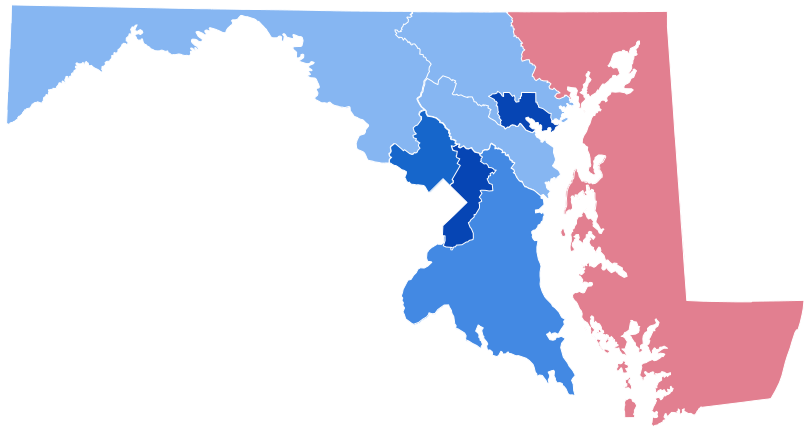

The U.S. Department of Labor, which runs the H-2B visa program, did not establish covid safety rules for the workers’ cross-country travel. Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina — states with flourishing seafood industries that rely on H-2B seafood workers — also failed to provide H-2B workers with pandemic protections.

Between October 2019 and September 2020, more than 12,000 H-2B workers were authorized to work at U.S. seafood companies, according to an analysis by the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at the University of Maryland.

Since January 2020, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration received 63,455 workplace complaints related to covid-19. Of those complaints, 32 were against seafood-processing companies. “If [workers] complain, they could be fired in retaliation and lose their lawful status in the U.S.,” said Clermont Ripley, an attorney for the nonprofit North Carolina Justice Center.

In the absence of government standards and enforcement, decisions on how to keep workers safe from covid-19 are largely left up to their employers.

Each season, H-2B workers travel from their hometowns in Mexico to U.S. consulates that approve their visas. They may wait days, if not weeks, in crowded rooms for their visas to process, then board crowded vans and buses for their trips north. Workers risk contracting covid-19 at each stage of this process.

After arriving, workers typically enter group housing provided by their employers — often at a weekly rate the workers pay. Some start work the next day without being tested for the virus. There is no requirement that workers be tested for covid-19 when they arrive, nor while they are in transit.

Holes in the regulatory system prompted worker-advocacy organizations to write in April 2020 to key agencies seeking immediate protection for these workers. None of the recommendations were adopted.

The Howard Center also found that Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina have not established local protections for H-2B workers that advocates say are needed.

In Maryland, 50 seafood workers contracted covid-19 last summer, according to the Dorchester County Health Department. The agency declined to disclose the locations, citing confidentiality laws. Those testing positive last July included seven H-2B crab pickers at Lindy’s.

Aubrey Vincent, vice president of Lindy’s, said the company had implemented safety measures in response to the pandemic. Masks are provided to workers, they are distanced six feet apart and sanitation procedures have been increased.

Yet this year, when 59 H-2B workers arrived in Maryland after two days of cross-country travel, Lindy’s put them to work the next day. Vincent said the decision was based on discussions with state and county health officials.

“They’ve already ridden in a bus all the way here,” Vincent said. “They’re already in the houses. They have already been exposed with each other. Why is working the issue, if that’s not where the contamination is happening?” she asked.

According to Vincent, the recruiter in charge of finding H-2B workers for Lindy’s said workers would be tested before crossing the U.S.-Mexico border. However, a negative covid-19 test is not required for travel into the U.S. by land, according to the U.S. consulate in Mexico.

Last July, a coalition of health professionals, including former OSHA officials and migrant-worker advocates, urged Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan to create an emergency temporary standard, which would require workplace steps to prevent covid-19 spread.

A spokesperson for Hogan told The Baltimore Sun in August that such standard was not needed, because the governor gave local health officials the authority to close down unsafe workplaces.

Asked by the Howard Center how many workplaces had been closed down, a spokesperson for the Maryland Department of Health wrote that the agency does not maintain a central database of companies cited by local health departments and law enforcement for not complying with covid-19 orders.

In March, senators from Maryland and Virginia sent a letter to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, urgently requesting more H-2B workers before April 1 — when the new crabbing season would begin in Maryland and Virginia. In April, Maryland’s governor requested that DHS immediately increase the number of H-2B worker visas to the maximum allowable under federal law. On April 20 — the same day the 59 H-2B workers arrived at Lindy’s — DHS announced it would make an additional 22,000 H-2B visas available this year.

“The H-2B program is designed to help U.S. employers fill temporary seasonal jobs,” said DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas, “while safeguarding the livelihoods of American workers.”

This story was produced by the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at the University of Maryland’s Philip Merrill College of Journalism, an initiative of the Scripps Howard Foundation in honor of the late news industry executive and pioneer, Roy W. Howard. It has been edited for length.

Vanessa Sánchez Pulla and Brittany Nicole Gaddy reported from Maryland and Virginia. Luciana Perez Uribe Guinassi reported from North Carolina and provided data analysis along with Aadit Tambe. Carmen Molina Acosta and Sophia Sorensen reported from Maryland. Trisha Ahmed reported from Maryland and wrote this story. Also contributing: Natalie Drum, Molly Castle Work, Elisa Posner, Kara Newhouse, Nick McMillan, Rachel Logan and Sahana Jayaraman

Common Sense for the Eastern Shore