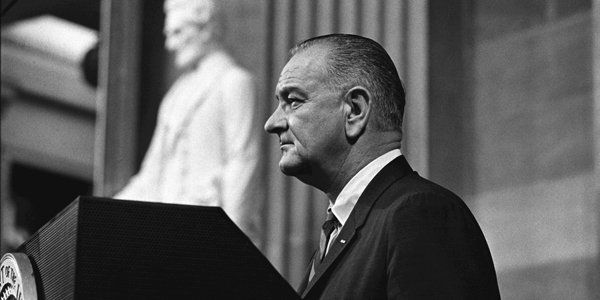

What Did Lyndon Johnson Really Think of Me?

In the fall of 1966, Wayne Hayes was one of the most powerful members of the House of Representatives. He was also well known as a mean-tempered bully. Nonetheless, he was an extraordinarily important ally for LBJ in the enactment of his legislative program, and in that milieu I became entangled with him.

Then a presidential assistant, I was in Paris where I had been invited to a cocktail party at the residence of the American ambassador. I found myself standing on the fringe of a group of Frenchmen being regaled by a very drunk Congressman Hayes. I listened, aghast, as he loudly excoriated Lyndon Johnson, slurring such slanders as, “If you knew him as I do, you would know he can’t be trusted.” And, “he is a rotten president! Don’t any of you ever forget that!”

I could not remain silent. Without thinking, I stepped forward and confronted Hayes, stating that, considering his position, he should not be saying things like that, especially in Paris in front of foreign dignitaries. Flushed with anger, Hayes demanded to know who I was, and I told him. “You and your boss can just go to hell,” he barked, and strode away.

The whole incident was upsetting, but I was totally surprised by what happened next. Back in my hotel room, I was sound asleep when I was startled awake by the telephone. It was Wayne Hayes, and, without preliminary, and still sounding drunk, he began shouting, “You are going to be fired, you son of a bitch. As soon as I get home, I’m calling Lyndon and that will be the end of you.” With that, he hung up, and I went back to sleep.

But that wasn’t the end of it. The moment I walked back into the White House, the president summoned me to the Oval Office.

“What the hell did you do to Wayne Hayes?” he asked, and I told him, thinking he’d be pleased that I had defended him. He was not. “We need his help,” Johnson stated, “and you will do whatever it takes to make it right with him. Of course, I’m not going to fire you. Nobody up there can make me to do that. But you are going up to his office right now, and you are going to apologize to him. More than that, you are going to make him believe that you mean every word you say.”

And that’s what I did. When I walked into Hayes’s office, he was scowling at me from behind his desk. “I suppose you are here to beg to get your job back,” he growled. “No, sir,” I answered in the softest voice I could muster. “I came here to tell you how wrong I was in Paris. I should never have said those things. I mean that from the bottom of my heart,” I added.

It was like magic. Hayes’ face broke into a broad smile. “Sit down, sit down,” he urged. From that moment and for the next hour, he regaled me with personal anecdotes as if I were his new best friend, including telling me how much he admired Lyndon Johnson.

Throughout, I continued to grin and nod my agreement. But when I reported all this to a pleased LBJ, I was still feeling sick about what I had just done. Still, I felt no joy when, 10 years later, Hayes became embroiled in a very public sex scandal that drove him from public office.

In November 1967, I discovered that the best and the worst of my relationship with the president could occur within one 24-hour period.

The war in Vietnam was going badly. Johnson could not appear in public anywhere but military bases without enduring demonstrations against him. Robert McNamara, his Secretary of Defense, was having a breakdown because of the war, and wanted to quit. The president badly needed a weekend off, and he decided to do that in Colonial Williamsburg in nearby Virginia. He asked me to arrange it, which meant a place for him to stay, a round of golf with his son-in-law, Chuck Robb, and church on Sunday.

And so, along with a detail of Secret Service agents, I drove to Williamsburg a couple of days in advance. My first call was to Arkansas Gov. Winthrop Rockefeller, whose family had largely financed the historic facility. A house for the Johnsons and a golf time were easily secured. I then asked Rockefeller if he would recommend a church for the president to attend, and he told me that the Williamsburg Episcopal Church headed by the Rev. Cotesworth Lewis would be perfect.

“Will there be a Vietnam problem with the reverend?” I specifically asked. “No way. He strongly supports the president,” Rockefeller answered.

To be absolutely certain — and accompanied by a Secret Service agent — I called upon Reverend Lewis, who reassured us concerning any Vietnam issue. He even handed us a copy of the sermon he would give, which was perfectly acceptable.

The evening prior to his going to that church, the president called me into the softly lighted study where he was sitting alone. He was in a reflective mood and he invited me to join him. Then, quietly, he began to talk, sharing with me some of his dreams for a better America and his despair with the never-ending war that seemed to be destroying everything. I did not say much, just stayed with him, soaking in the feeling that this was a very special moment.

The next morning, the president and his family went to church. Instead of joining them, I waited outside, standing behind the last car in the waiting presidential motorcade. Suddenly, the church doors burst open and a gaggle of media people rushed out, shouting, “You’ll never believe what just happened in there!”

Instinctively, I knew all too well, and my heart dropped. A few moments later, I learned that the reverend had lied to me. He had abandoned the text of the sermon and instead had spent the time lecturing the helplessly sitting president about the evils of the Vietnam War.

When the president walked out the church door, he turned his head, spotted me, and with a bend of his finger summoned me to join him. And so I walked to his limousine, wishing only that the earth would swallow me up.

Thus began the most miserable six days of my life. In Johnson’s eyes, the main person to blame was not the reverend, but me for permitting it to happen. Sitting in the limousine, the president of the United States lit into me with total fury. The fact that I had anticipated the danger and had done what I could meant nothing. Nor that the Secret Service agent was with me throughout. In Johnson’s eyes, I should have seen through the reverend’s falsity, to which I had no answer.

The president’s diatribe against me continued back at the house and, following that, after he returned from his golf game. Even then it did not end. He ordered me to fly back to the White House with him, and, throughout that helicopter trip and even at the mansion, my ordeal continued without letup.

When I finally reached home, I saw that coverage of the church fiasco was all over the television networks, and the next morning it was splashed across the front pages of both the Washington Post and New York Times. It seemed that the reverend had achieved his 15 minutes of fame.

Right then, even though the president had not yet asked for it, I believed that I had no choice but to resign. When I returned to the White House, I immediately began to dictate that letter, but before I could finish, Marvin Watson, the president’s chief of staff, walked into my office. He saw what I was doing and told me to stop. “Don’t quit,” he said. “The president will calm down. Just wait him out.” At that moment, with all my heart I wanted to resign, but I listened to Marvin and didn’t.

I heard nothing more from the president that day, nor did I see or talk to him for the rest of the week.

Then, on the following Saturday, I was invited to a formal White House dinner honoring another nation’s head of state. With great trepidation, I went. Arriving there, I took my place in the traditional receiving line, having no idea what would occur when I reached the president.

What happened was this: The president grabbed my arm and pulled me close. Then he said to the visiting head of state, “I want you to meet this young man who is one of the finest assistants anyone could ever have.”

So, in the end, what did the president think of me? Perhaps it is expressed in the words he wrote to me by hand in his black Sharpie pen in September 1968 when I left the White House to join my law firm:

“NO ONE IN W.H. WAS MORE DEDICATED TO COUNTRY OR MORE LOYAL TO IT. THANKS MUCH AGAIN.”

A long river of years has passed since President Johnson wrote those words. Yet, even today, I remain warmed by them. I had the great honor of serving in the White House. It was very much worthwhile.

Sherwin Markman, a graduate of the Yale Law School, lives with his wife, Kathryn (Peggy) in Rock Hall, Maryland. He served as an assistant to President Lyndon Johnson, after which was a trial lawyer in Washington, D.C. He has published several books, including one dealing with the Electoral College. He has also taught and lectured about the American political system.

Common Sense for the Eastern Shore