A New Congressional Map for Maryland

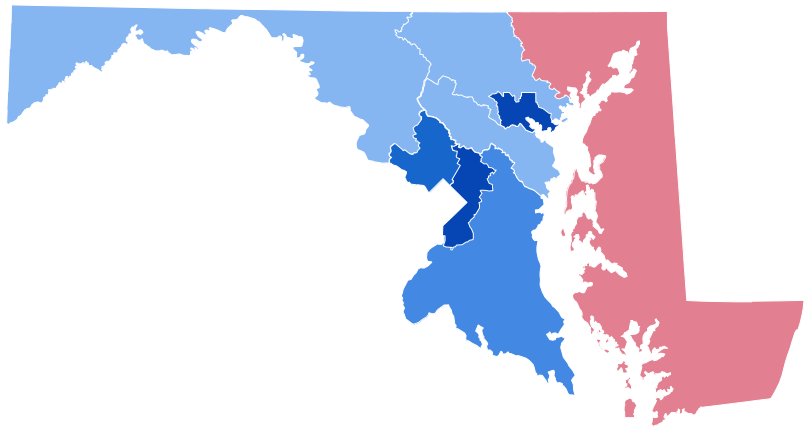

New Congressional district map for Maryland. Source: Maryland Department of Planning

The drama over Maryland’s congressional redistricting has ended.

In accord with the U.S. Constitution, the boundaries of Maryland’s eight congressional districts are redrawn every 10 years to reflect shifts in population as determined by the federal census. The same drama plays out in almost every state, with the exception of Alaska, Delaware, North and South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming; their populations are so small that they’re entitled to only a single, state-wide representative. And, as anyone who follows the news is aware, it’s an opportunity for political parties to draw maps contrived to maximize their power for the next few elections, a process known as gerrymandering.

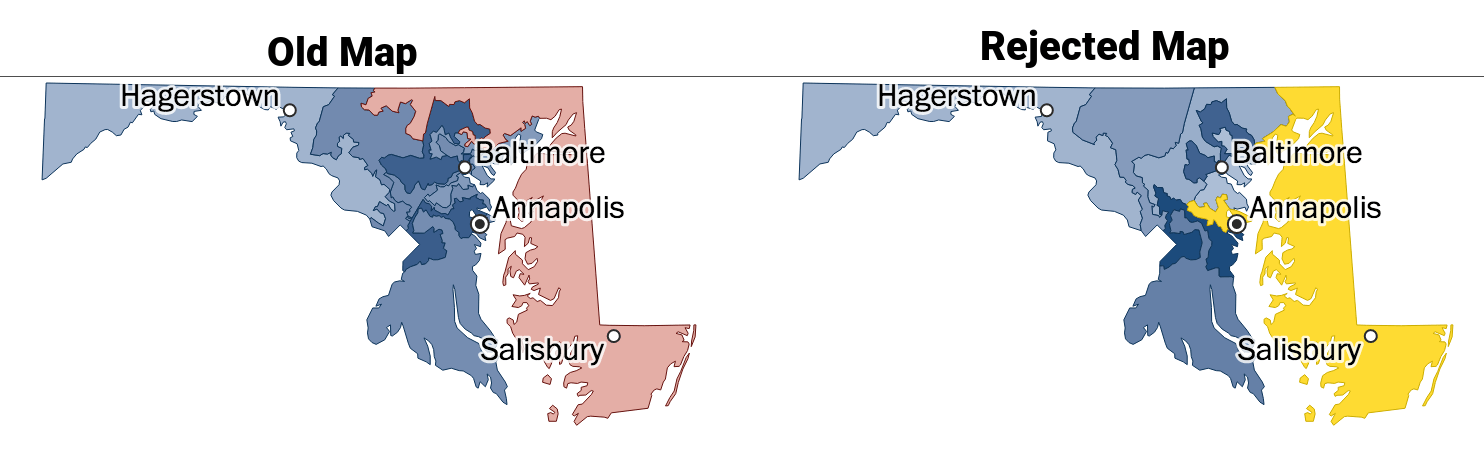

A redistricting map was enacted by the Maryland General Assembly in December and vetoed by Gov. Larry Hogan, with his veto then overridden by the Democrat-dominated legislature. In that map, the First District — the only district currently represented by a Republican — would have added parts of Anne Arundel County to its Eastern Shore base. That would have increased the number of Democratic voters in the district, making it more competitive, and possibly even allowing a Democrat to win the House seat. At the same time, the map would have preserved the seven solidly Democratic districts in the rest of the state.

But on March 25, Anne Arundel County Senior Judge Lynne A. Battaglia ruled that the map was an extreme partisan gerrymander that violated the state constitution’s requirement for districts to be compact and follow existing political subdivisions. Looking at the districts’ shapes, especially in the central part of the state, it’s hard to fault her decision. Some of the districts — crafted to retain incumbents’ strongest supporters — were undeniably serpentine, practically a textbook illustration of “gerrymanders.”

Old Congressional map and rejected Congressional map. Source: Maryland General Assembly

The judge’s ruling put the ball back in the Democrats’ hands, with only five days to meet a March 30 deadline to adopt a new map. Scrambling to meet the date, the Democrats approved a considerably different map that addresses the judge’s objections.

Attorney General Brian Frosh, also a Democrat, added another complication by appealing Battaglia’s decision. He argued that the constitutional requirement she cited applies only to state offices, not to congressional districts. But when the Democrats’ second map was quickly signed into law by Hogan on April 4, Frosh withdrew his appeal. Barring an unexpected turn of events, the new map should be in effect until after the next census, in 2030.

The revised map returns the First District to its solid-red configuration, adding all of Harford County and part of Baltimore County to the nine Eastern Shore counties. Previously, only parts of Harford were included in the district. The new map also reconfigures several districts in the center of the state into more compact shapes. Two districts bordering Baltimore City move from strongly Democratic to leaning Democrat, according to analysis on the FiveThirtyEight.com website. And in the westernmost part of the state, the Sixth District is ranked highly competitive, opening the possibility of a second Republican member of Congress from Maryland.

This won’t, however, end the wrangling over election districts. Another redistricting case, involving the district lines for the House of Delegates and the state Senate, is awaiting a decision from the Maryland Court of Appeals. A special magistrate has recommended that the challenges be dismissed, but a final decision may not be made before April 13, which the court set as a deadline for any exceptions to the magistrate’s ruling.

The delays in approving a map have moved back the entire election schedule. The filing date for state and federal offices, originally in February, is now April 15. The primary election is set for July 19. But both could again be delayed if the Court of Appeals decides to invalidate the district map for state offices.

For now, the redistricting drama is over, at least at the Congressional level. Until 2030, that is.

Peter Heck is a Chestertown-based writer and editor, who spent 10 years at the Kent County News and three more with the Chestertown Spy. He is the author of 10 novels and co-author of four plays, a book reviewer for Asimov’s and Kirkus Reviews, and an incorrigible guitarist.

Common Sense for the Eastern Shore