Child and Teen Firearm Mortality in the U.S. and Peer Countries

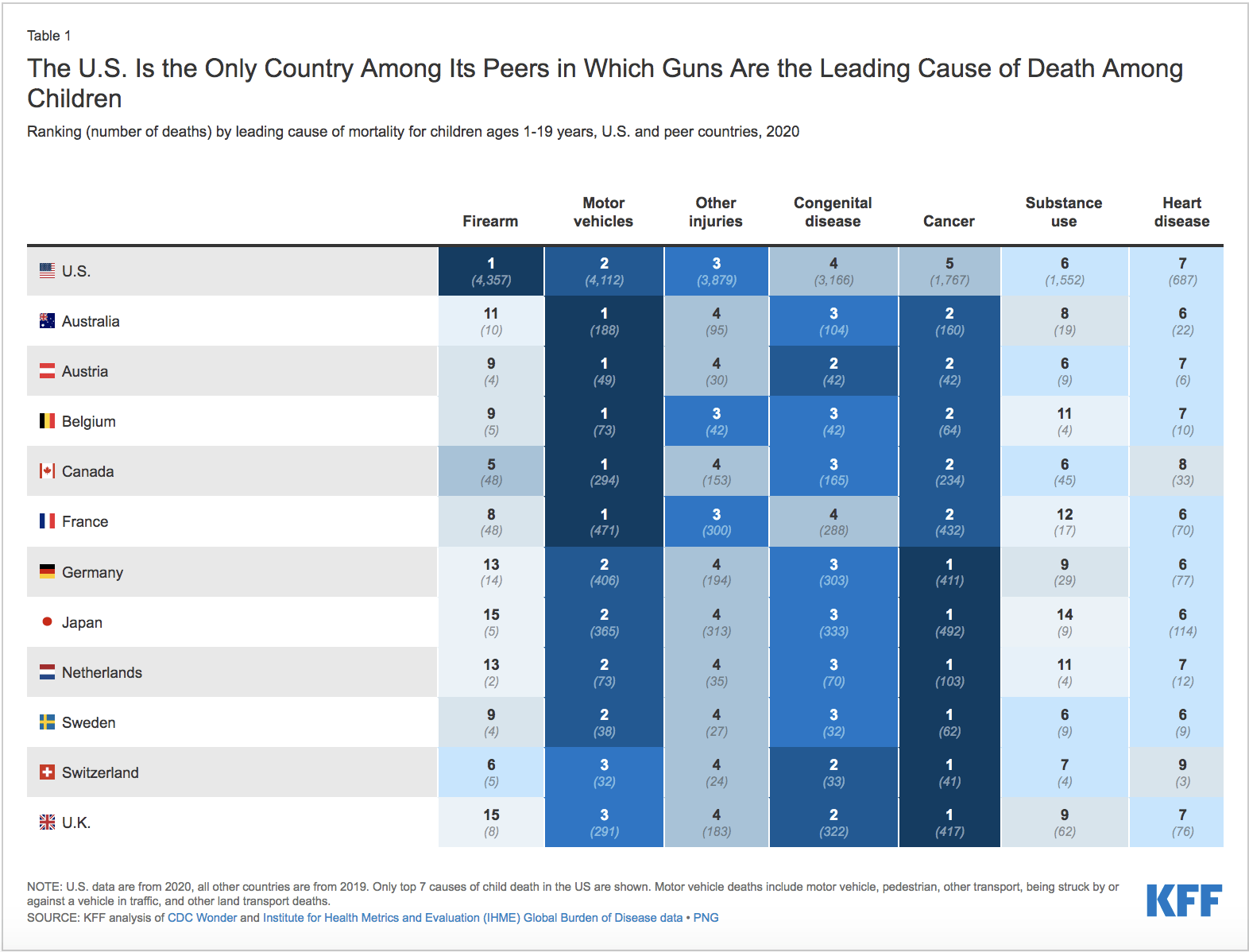

Firearms recently became the No. 1 cause of death for children in the United States, surpassing motor vehicle deaths and those caused by other injuries.

In 2020 (the most recent year with available data from the Centers for Disease Control), firearms were the No. 1 cause of death for children ages 1-19 in the United States, taking the lives of 4,357 children. Except for Canada, in no other peer country were firearms among the top five leading causes of childhood deaths. Motor vehicle accidents and cancer are the two most common causes of death for this age group in all other comparable countries.

Combining all child firearm deaths in the U.S. with those in other Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries with above median Gross Domestic Product and GDP per capita, the U.S. accounts for 97% of gun-related child deaths, despite representing 46% of the total population in these similarly large and wealthy countries. Combined, the 11 other peer countries account for only 153 of the total 4,510 firearm deaths for children ages 1-19 years in these nations in 2020, and the U.S. accounts for the remainder.

Firearms account for 20% of all child deaths in the U.S., compared to an average of less than 2% of child deaths in similarly large and wealthy nations.

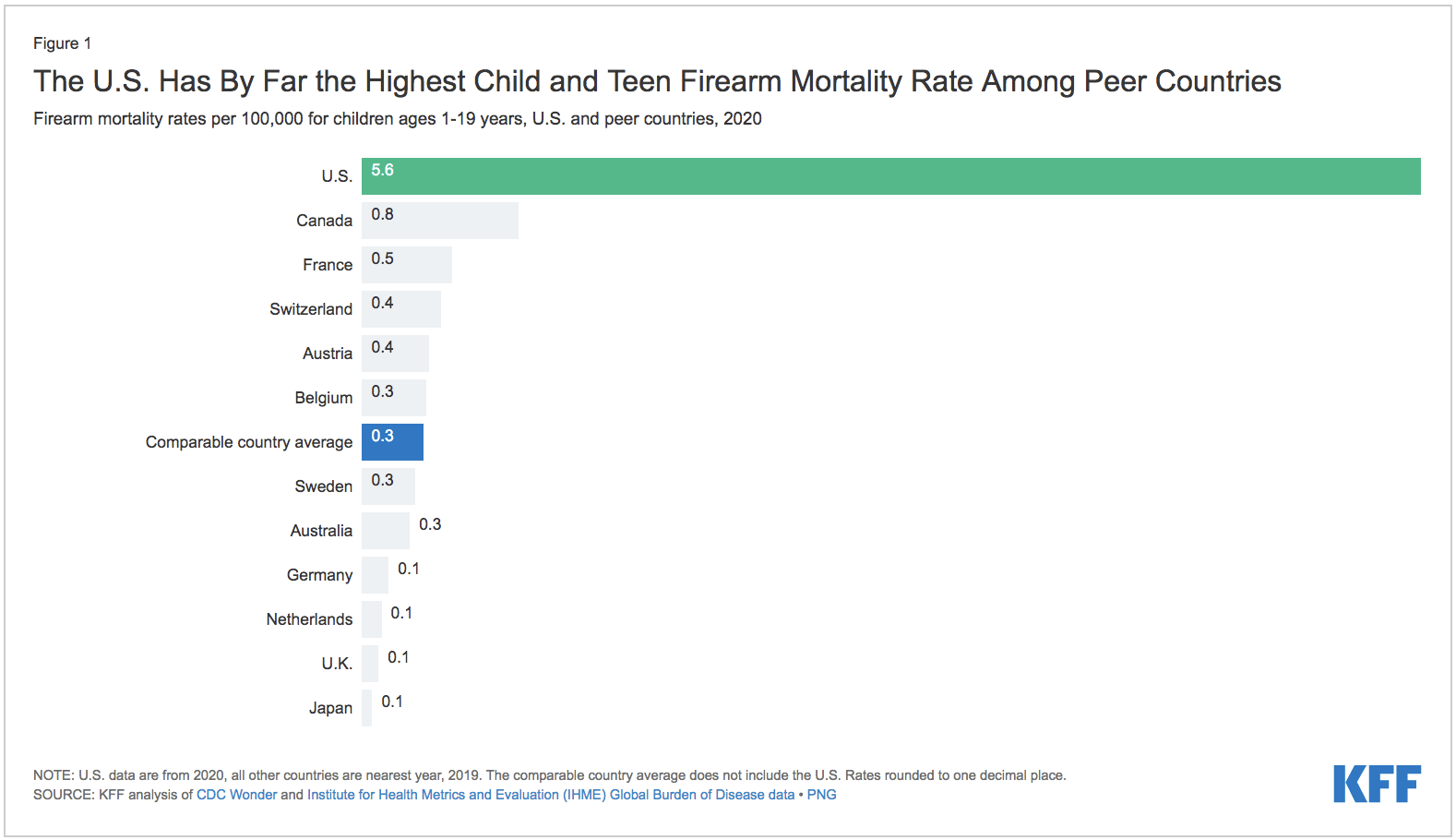

On a per capita basis, the firearm death rate among children in the U.S. is about 7 times the rate of Canada, the country with the second-highest child firearm death rate among similarly large and wealthy nations.

If firearm deaths in the U.S. occurred at rates seen in Canada, we estimate that approximately 26,000 fewer children’s lives in the U.S. would have been lost since 2010 (an average of about 2,300 lives per year). This would have reduced the total number of child deaths from all causes in the U.S. by 12%.

After reaching a recent low of 3.1 firearm deaths per 100,000 children in 2013, the U.S. saw an 81% increase — to 5.6 firearm deaths per 100,000 children — by 2020, just seven years later.

The U.S. is the only country among its peers that has seen an increase in the rate of child firearm deaths in the last two decades, 42% since 2000. All comparably large and wealthy countries have seen child firearm deaths fall since 2000. These peer nations had an average child firearm death rate of 0.7 per 100,000 children in 2000, falling 56% to 0.3 per 100,000 children in 2019.

Not all firearm deaths are a result of violent attacks. In the U.S., in 2020, 30% of child deaths by firearm were ruled suicides, and 5% were unintentional or undetermined accidents. However, the most common type of child firearm death is due to violent assault. 65% of all child firearm deaths are from assault.

The spike in 2020 child firearm deaths in the U.S. was primarily driven by an increase in gun assault deaths. The child firearm assault mortality rate reached a high in 2020 with a rate of 3.6 per 100,000, a 39% increase from the year before. The firearm suicide mortality rate among children in the U.S. increased 13% from 2019 to 2020, 31% since 2000, and 89% since the recent low in 2010.

Not only does the U.S. have by far the highest overall firearm death rate among children, the U.S. also has the highest rates of each type of child firearm deaths — suicides, assaults, and accident or undetermined intent — among similarly large and wealthy countries.

The U.S. also has a higher overall suicide rate among peer nations regardless of whether a firearm is involved. In the U.S., the overall child suicide rate is 3.6 per 100,000 children, and 1.7 per 100,000 children died by suicide from firearms. In comparable countries, on average, the overall child suicide rate is 2.8 per 100,000 children, and 0.2 per 100,000 children died by suicide from firearms. If the U.S. child firearm suicide rate was brought down to 0.2 per 100,000 children (the same as the average in peer countries), 1,100 fewer children would have died in 2020 alone.

Exposure and use of firearms also has implications for children’s mental health. Research suggests that children may experience negative mental health impacts, including symptoms of anxiety, in response to gun violence.

KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation) is a nonprofit organization focusing on national health issues, as well as the U.S. role in global health policy. KFF develops and runs its own policy analysis, journalism and communications programs, sometimes in partnership with major news organizations.

Common Sense for the Eastern Shore