Progress on Restoring Oyster Reefs in Chesapeake Bay and Eastern Shore Rivers

For thousands of years before Europeans arrived in North America, the first Americans fished and hunted in and around the Chesapeake Bay. Along with numerous varieties of fish, these indigenous people also prized oysters.

Oysters are a keystone species, meaning that they are essential to many other species and for the general health of the Bay. Originally, the Bay had massive reefs, built from the shells of generations of oysters. These reefs provided habitat for many other species. In addition, oysters via their filter-feeding help to keep the Bay’s water fresh and clean. A single oyster can filter up to 50 gallons of water every day, removing toxins and debris.

In those early days, the waters of the Bay were filled with oysters, a seemingly endless supply. When the early European settlers began arriving, the Chesapeake Bay quickly became an important food source and economic driver for the colonies.

However, over the decades the number, variety, and size of the Bay’s aquatic species declined. This trend sped up increasingly in the 1800s and 1900s as commercial fishing grew and more efficient techniques such as tonging and dredging were developed. The oyster reefs suffered great damage which also affected the other species that depended on the reefs, including crabs, eels, seagrass, and many varieties of fish. Reefs vanished or were greatly reduced in size.

By the late 1800s, over-fishing along with various forms of pollution had significantly reduced oyster the population in the Chesapeake Bay. Over the next hundred years or so, pollution from agricultural fertilizers, gasoline engines, and factory chemicals all contributed to the decline in the Bay’s abundance.

Today it’s estimated that the oyster population is a mere one to three per cent of its levels in the late 1500s and early 1600s when Europeans began to colonize the Chesapeake Bay area.

As this became apparent, both government and conservation organizations started programs to protect and restore the Bay. It has been a long haul and only recently has there been much progress. There is still a long way to go but projects to rebuild the oyster reefs and oyster populations have begun to make some significant progress.

One oyster sanctuary and reef restoration in Maryland was started in 2011 in Harris Creek on the Eastern Shore. The project showed almost immediate improvement in the oyster population. This proof of concept encouraged the involved parties to expand their efforts.

Thus in 2014, the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement was signed, extending a partnership between governmental and private organizations that had been working on oyster reef restoration. Organized by the Chesapeake Bay Program, the cooperating partners include, among others, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and the six states — Delaware, Maryland, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia, plus Washington, D.C. — that are part of the Chesapeake Bay Watershed.

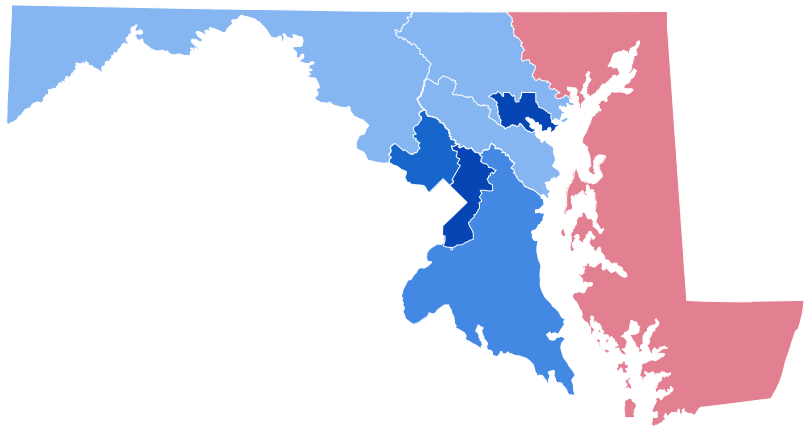

The projects focused on 10 tributaries of the Bay — five in Maryland and five in Virginia. Four of the five Maryland oyster reservations are in rivers on the Eastern Shore.

In Maryland, the tributaries are Harris Creek and the Tred Avon River in Talbot County, the Little Choptank River in Dorchester County near Cambridge, and Manokin River in Somerset County. The fifth is the St. Mary’s River on the Western Shore of the Chesapeake Bay. Harvesting of oysters is prohibited in these sanctuary areas.

Reef restoration is nearly completed in the first three while work on the Manokin River oyster sanctuary, which began in 2021, is ongoing. Monitoring of oyster population and the measuring of other aspects of Bay health will continue even after the initial rebuilding of the reefs is completed.

The plan is to restore over 2,300 acres of oyster reef habitat in the two states — an ambitious undertaking, making it the world’s largest oyster reef restoration project.

As of 2024, that target has almost been met, with 1,572 acres of healthy reefs established in eight of the ten Bay tributaries. The remaining acres are in the Lynnhaven (Virginia) and Manokin (Maryland) rivers.

While significant progress has been made in restoring oyster reefs, the projects have not been without some skepticism and controversy. The required permits for various aspects of the projects have often been difficult to obtain. For example, a federally funded restoration project in the Tred Avon River was delayed for several years over its proposed use of granite to build reefs. Natural oyster or clam shells are the preferred building materials, although granite has been used successfully in other reef restorations. Objections by some watermen and conservationists were finally lifted after the Army Corps of Engineers explained that there simply weren’t enough clam shells available to finish the job within the allotted time frame.

There has also been controversy over dredging shells from reefs such as the Man O’ War oyster reef near Baltimore. This reef is one of the few remaining ancient oyster reefs; however, it is no longer productive. Proponents of dredging said that it could provide millions of bushels of old oyster shells from its almost 450 acres according to a 1988 survey. The Man O’ War reef is a popular fishing and boating area, and many anglers and conservationists protested the dredging.

There have also been worries about potential incompatibilities of the various construction materials as well as fears of introducing diseases and toxins or disturbing nearby aquatic habitats.

One of the many reasons that that oyster shell reefs have declined is that so many oysters from the Chesapeake Bay have been exported to other countries, especially to Japan and other countries in Asia where Maryland oysters are considered a delicacy. To keep the oysters fresh on such long trips, they need to remain in the shell on ice in refrigerated containers.

When oysters are transported relatively short distances, a few hours by plane or truck, they can be shucked at processing plants near the Bay and sent on ice without their shells. The shells then are often discarded back into the water where they contribute to reef building. But now in an interesting turn of events, some Asian oyster shells — a slightly different genetic variety that floated or hitchhiked on boats from Asia to the Pacific coast of the U.S. and built oyster reefs there — will be arriving from a seafood plant in Washington State to help rebuild the oyster reefs of the Chesapeake Bay. After settling some disagreements over their safety and suitability for the Bay, 84 truckloads of Asian oyster shells will be deposited in the Bay by the end of summer 2024. Global commerce comes full circle with Chesapeake Bay oyster shells going to Asia and Asian oyster shells coming to the Bay.

All in all, the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement’s ten oyster reef restoration projects appear to be well on the way to a successful completion by their target date of the end of 2025.

Jane Jewell is a writer, editor, photographer, and teacher. She has worked in news, publishing, and as the director of a national writer's group. She lives in Chestertown with her husband Peter Heck, a ginger cat named Riley, and a lot of books.

Common Sense for the Eastern Shore