The Filibuster: Pirates to Politics

Does it ever seem that our congress has been hijacked? That nothing gets done? That bills and budgets are not passed, that nominees are not confirmed, that we’re always at war but war is never declared, or that the government is in gridlock or even shut down because no one can agree or compromise? We tend to blame it on a decrease in civility in every aspect of society, on an increase in partisan politics, or on unethical, egotistical, power-grabbing politicians. Now these are surely factors. But often, especially in the Senate, the problem is baked into the system. Enter the filibuster.

Today we know the filibuster as a technique to delay or block the passage of a bill. It is generally used by a single senator—or sometimes a group of senators—who are passionately opposed to a particular bill but realize that they don’t have the votes to stop the bill. While any tactic that will obstruct, stop, or delay the process is technically a filibuster, the most commonly used filibuster tactic is to prevent the bill from coming to a vote by just keeping the debate going endlessly. In other words, by “talking it to death.”

Senators can do this because of a peculiar combination of Senate rules and traditions. First of all, they are allowed to speak as long as they want, without interruption, on any subject. Thus, they can go on for hours, taking turns if there are several of them, or, when it’s a single senator, giving marathon speeches that are hours-long and that may include telling jokes or reading from the phone book and the Bible. The longest single-Senator filibuster was 24 hours and 18 minutes, given by Strom Thurmond in 1957 in an attempt to stop a civil rights bill. The filibuster has most frequently been used on legislation regarding hot-button issues including the budget, civil rights, and the military. Filibusters have been very effective in stopping or amending controversial laws although they also fail frequently to do more than delay the inevitable. Often the mere threat of a filibuster is enough to cause the proposed bill to be dropped completely, at least for that session of congress.

This kind of delaying tactic can’t happen in the House because their rules include various limits on debate, the first of which was established in 1811. Then in 1842, the House permanently abolished unlimited debate. However, the Senate, despite an increasing use of the filibuster during the 1800s, refused to adopt any limit at all on debate until 1917. Then, during America’s growing involvement in World War I, President Woodrow Wilson became exasperated with the Senate’s interminable debate and inability to decide on important issues regarding the war. Wilson publicly castigated the Senators, calling them a “little group of willful men” who “rendered the great Government of the United States helpless and contemptible.” This motivated the Senate, in a patriotic fervor, to pass Rule 22, known as “cloture” which allowed 16 senators to sign a petition calling for an end to debate. Then if 2/3 of senators voted “aye,” debate would be limited to just 30 more hours, after which a vote must be held. In the 1970s, that was lowered to 3/5 of senators, which meant 60 senators must vote in favor to end a filibuster. Cloture, however, is difficult to get.

It’s an odd irony of history that the potential for the Senate filibuster was created accidentally in 1806 based on a suggestion made a year earlier by Aaron Burr, then Vice-president of the United States and therefore the official tie-breaker for the Senate.At that point Congress was still developing its rules and traditions. During one session concerning the rules, Burr suggested dropping the then current rule that allowed any member to call “the previous question,” which meant to call for a vote on whatever measure was under discussion at the time. Under that rule, whenever “a vote is called,” the debate stops and a vote must be taken. The motion then passes or fails.

While this obstructive practice of marathon speeches was used by the Romans and probably by every legislative body in every era, the term “filibuster” was not used for the technique until the mid-1800s. Originally, the term came from the Dutch word vrijbuiter , meaning “pirate” or “freebooter.” The similar Spanish term, filibustero , was used to refer to pirates or adventurers who tried to take over a region, country, or government through mainly non-military but generally illegal and/or devious methods. The odd linguistic parallel here is that Aaron Burr who made the Senatorial filibuster possible was himself charged and brought to trial for a “filibuster” as the word was used in the 1700s and early 1800s in a political version of the Spanish and Dutch sense of an unauthorized hijacking or “pirate take-over.” Burr had raised money and support for an attempt to take over parts of US and Spanish territory including Florida, Louisiana, and Texas, with the goal of creating a new country—which, of course, he would be in charge of. Burr was acquitted of this pirate filibuster but the other filibuster that he created lives on.

The filibuster does more than just delay or stop a bill. It also brings attention and publicity to an issue that may not have been high on the public or political radar. This heightened awareness can result in changing opinions or the opposite, hardening opinions. Filibusters can—and have—resulted in compromises that would not have happened otherwise. These compromises may include the dropping of certain clauses in the bill or the addition of amendments, or significant increases or decreases in the funding provided in the bill. Those who favor the filibuster claim that it protects the minority from the tyranny of the majority. Those opposing claim that the filibuster actually promotes tyranny by a minority and blocks the will of the people. Which side of that divide individuals fall on usually depends on whether they are in the majority or the minority at the time. Although there have been many attempts to reign in the filibuster and some limiting rules such as the cloture Rule 22 have been adopted, the Senate has declined to abolish the filibuster as the House has. They realize that they may want it when they are next in power.

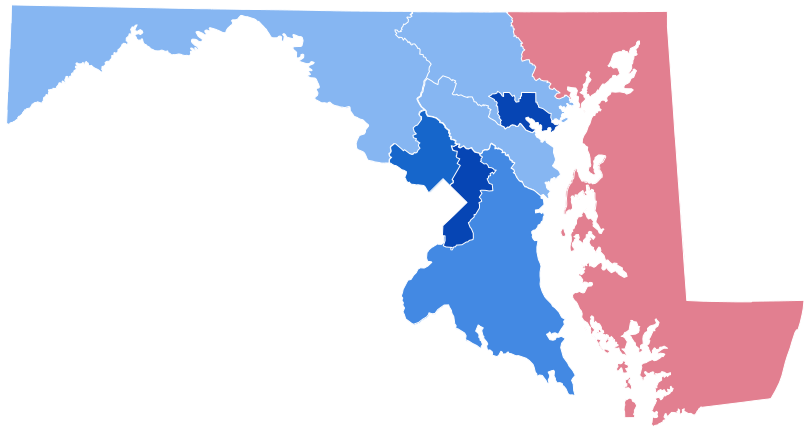

Common Sense for the Eastern Shore